|

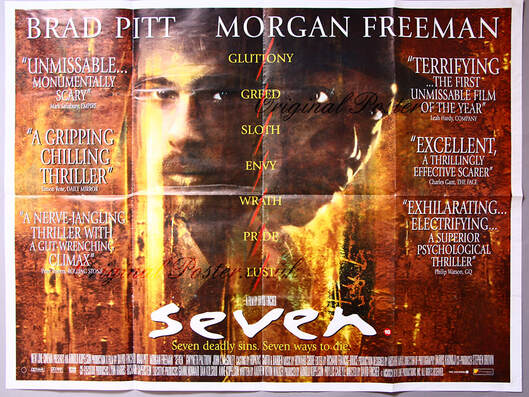

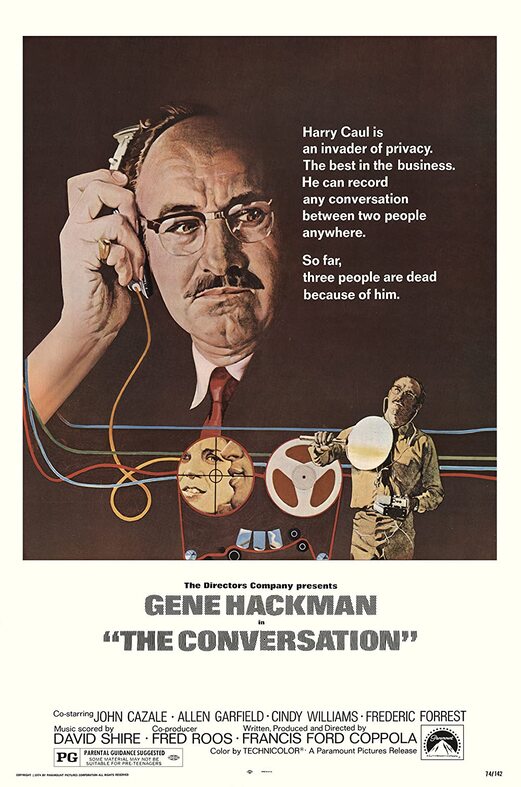

By Ian Long "As a controlling force in human affairs, motivation is pretty well shagged out by now. It hasn’t got what it takes to motivate people any more.” – Martin Amis, Money (1984) The 'serial killer' has become a cliché of loose thinking and bad writing. Simply invoking the phrase can be seen as sufficient to create an all-purpose, off-the-peg bogeyman capable of shading stories with a pall of ersatz evil, for which little creative or psychological investment is required. It’s understandable that many writers are reluctant to look beyond the words to explore the reality they describe. We all are. Because if it’s horror you want, there isn’t anything much worse than someone who views other human beings as disposable material for his personal gratification, and is prepared to order his entire life to this end. The ‘serial killer’ exists on a lower moral plain than other murder-adjacent movie archetypes like the ‘bounty hunter,’ the ‘vigilante,’ the ‘gangster,’ even the ‘hitman.’ To say something meaningful about this kind of individual – merely to provide a credible portrait of one of them – requires a descent into the darkest recesses of the psyche. The Behavioral Science Unit In the late 1970s, the prime movers behind the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit were prepared to make this descent, and – in lightly fictionalised form – they provide the protagonists of David Fincher’s Netflix series Mindhunter (2017-2019). It was the BSU which actually coined the term ‘serial killer,’ providing a conceptual framework to help the group profile and track down the ‘new’ kind of murderer they’d identified – and, ideally, to prevent them from offending in the first place. So what conclusions does Mindhunter draw about ‘serial killers’? And what hints does the series give us on how to approach them from a writing point of view? Dirty, hazy yellow In style and theme, Mindhunter is an elaboration of Fincher’s 2007 film Zodiac, which focused on the perpetrator of a sequence of murders over a period of years in the San Francisco Bay area (the Zodiac Killer was still active at the time in which Mindhunter is set, and his identity has never been satisfactorily established). The series shares Zodiac’s predilection for visual fields of dirty, hazy yellow, its semi-abstract use of space, and its painstaking reconstructions of retro domestic and institutional environments – evocations so meticulous that Netflix cancelled the show’s third season because it was all just getting too expensive. Mindhunter also harks back to Fincher’s early film Se7en (effectively his debut after the mis-step of the quickly-disowned Alien 3), the movie which put him on the cinephile map as a talent to be watched. But for all its state-of-the-art imagery and baroque twists, Se7en was complicit (along with the Hannibal franchise) in elevating the 'serial killer' to the status of evil genius whose intellect effortlessly dwarfs that of the cops on his trail. Copycat killers Se7en and Silence of the Lambs triggered a slue of cinematic copycats. Repeat murderers showed up all over the landscape of film and TV (where would Nordic Noir be without them?), each with a basket of strange obsessions, each killing according to some more or less implausible personal pattern. Untold numbers of further suspects linger in countless unproduced scripts. But Fincher himself had sobered up considerably by the time of Zodiac. The film tracked the personal sacrifices made by a man who becomes obsessed with bringing the titular killer to justice. The barely conclusive nature of his quest is mirrored by a long, tortuous narrative that risked draining the life from its audience even as it anatomised a very real psychological situation. This air of gravity persists in Mindhunter, which sidesteps numerous genre tropes. In contrast with the lingered-over, guignol death tableaux of Se7en, the crimes are relayed to the audience either verbally, or via briefly-glimpsed crime-scene photos. We don’t get to see the gruesomeness. But we are well aware it’s there. The protagonist Mindhunter’s central character is a young FBI man, Holden Ford. Intelligent and idealistic, ready to follow his intuition even if it means going against professional orthodoxy, Holden is nevertheless so uptight and buttoned-up that Jonathan Groff’s suit does much of the dramatic heavy lifting of his portrayal. An opening sequence shows Holden attending a hostage situation. Hampered by a dumb-bell, regulation-bound cop, he tries to talk down the psychotic captor. But despite Holden’s best efforts the disturbed man isn’t susceptible to intervention, and we watch from a grateful distance as he blows his head off with a shotgun. Later, Holden’s boss congratulates him on what he regards as an optimal result. No hostages were harmed, and the perp’s death is no great loss – maybe even a plus point. But Holden is far from satisfied. More could have been done. Much more. The dramatic challenge Seconded to the FBI Training Academy to teach hostage negotiation, Holden passes a seminar room where senior homicide investigator Wilson is presenting a master-class on the new kind of killer he’s identified. Holden listens, intrigued. After the talk he buttonholes Wilson, telling the older man he likes what he heard about ‘motiveless’ homicide. They continue the discussion over beers, and Wilson enlarges on how, post-Vietnam, post-Watergate, post-JFK, a fresh moral darkness has descended on U.S. society – and the minds of its criminals. “Yeah, I'm not saying there’s literally no motive,” he elaborates, “I'm saying it’s not a rational motive. We call it ‘aberrant behaviour’ because it’s unlike anything we’ve seen before. We can’t predict it because it’s, by nature, unpredictable. We can’t classify it, because it’s unclassifiable. It’s just somehow ‘evolved.’ This is the world Nixon bequeathed us. All bets are off.” Wilson’s words are a challenge to Holden, posing the questions that animate the entire series. Are all bets really off? Is this new generation of killer truly beyond comprehension? Or could there be ways to predict, classify, understand and combat them? The Paranoid Thriller Wilson’s words call to mind what’s now called the Paranoid Thriller subgenre. Around the time that Mindhunter is set, a cluster of outstanding films (Night Moves, Klute, Chinatown, The Conversation, The Parallax View and others) suggested that it was futile to try to understand criminal activity, political events, human motivations – perhaps reality itself. Each film features a protagonist who tries, and fails, to get to the heart of a crucial investigation of some kind, with each (non) resolution overturning genre expectations in ways calculated to unnerve audiences (Zodiac could be seen as a late flowering of the subgenre). Finding information Holden’s next fortuitous meeting is with Debbie, a young woman with a contradictory nature. On the one hand she has strong ‘manic pixie dream girl’ markers, giving Holden capriciously mixed signals while introducing him to punk rock, bongs and cunnilingus. However, she’s also a graduate sociology student and clues him up on Emile Durkheim’s theory that “all forms of deviancy are simply a challenge to the normalised repressiveness of the state.” But Holden isn’t into top-down theory. He wants information straight from the horse’s mouth. So he’s excited when a contact tells him about Edmund Kemper, a man who’s recently turned himself in to the police, confessing to numerous killings. When he learns that Ed is more than happy to talk about himself, Holden just has to go and meet him. The horse and his mouth Ed may be Mindhunter’s most memorable feature. A six-foot-nine slab of pallid flesh embodied by Cameron Britton in a disturbingly convincing manner (like all the killers we meet in the series), he is another bifurcated character. The crimes he’s committed are wilfully, militantly, atrocious; but he’s able to explicate his psychology and actions in such detached, meticulous terms that he’s as much well-informed, if weirdly affectless, college lecturer as deranged slayer. Over-excited, new to the craft of interviewing psychopaths, Holden injudiciously spills details of his relationship with Debbie to the impassive man-mountain, who’s more than capable of reversing the flow of inquiry to feel out the psychology of his interrogators. Nonetheless, Ed quickly becomes a touchstone for Holden’s nascent team. For by now, Holden has united with FBI agent and gruff family man Bill Tench (a traditionalist, but intelligent and open to new ideas) and writer and academic Wendy Carr (cool, analytical, a corrective to Holden’s wayward leanings) to inaugurate the Behavioral Studies Unit in earnest. Wendy hopes that the knowledge gleaned from their extreme cases will apply to her own study of white collar, but no less psychopathic, criminals. Initially repulsed by the idea of fraternising with the likes of Ed, Bill soon relents and joins Holden in further interviews, meanwhile struggling with the possibility that the wily narcissists they’re probing may well be manipulating them. A new kind of killer? Some surprises emerge from the interviews. The Son of Sam’s tales of demonic possession were probably concocted for the benefit of police, psychiatrists, and the general public. Manson may have been as much a follower as a leader: having cobbled together a litany of violent fantasies to entrance and subdue his ‘family’, Charlie had little recourse but to fall in line when they began to actually put them into practice. But what of Wilson’s suggestion that some new kind of killer was brewed in the chaotic crucible of the American 1970s? Compulsive sexual murderers with grotesque résumés similar to those we see in the series had been brought to justice decades before the 1970s. Ed Gein and Albert Fish are just two examples. But many more may never have been caught at all. If a killer chose his targets astutely, it could have been much easier to get away with killings in the days before mass media, when large, newly-arrived transient populations, often lacking a common language, were dispersing across a vast territory, and authorities were unable or unwilling to join the dots. And the fundamental causative factors for criminal psychopathology which the team uncovers are far from time-specific. Backstories of neglect, abuse, rejection, ostracism for perceived ‘difference,’ sadistic parents, social deprivation, and time spent in institutions feature strongly in the early lives of the killers they profile. Sad, certainly, but unexceptional, and definitely not confined to the 1970s. “Battle not with monsters” As the series continues, however, it becomes plain that while the BSU agents are looking into the abyss, the abyss is staring squarely back at them. Always rather introverted and humourless, Holden’s increasingly strident “ends justify the means” absolutism begins to alarm Bill and Wendy. And when the murder of an elderly woman whose investigation they’ve been reluctantly drawn into is followed by another, similar crime, his punching-the-air jubilation is truly jarring. Yes, the case now fits their remit of repeated killings, but is this really something to celebrate? The glacially competent Wendy marvels at one killer’s ability to “compartmentalise” his life, seemingly unaware of her repeated use of the same word to characterise her own choice of remaining a closeted Lesbian. Bill’s withdrawn adopted son Brian manifests traits similar to those of a neophyte psychopath, having participated in the killing of a baby by a group of other children. On top of all this, all three team members experience breakdowns in their intimate lives – having already established that dysfunctional sexual relations are one key indicator of psychopathology (Holden frequently reiterates that serial killers are incapable of living normal lives, holding down jobs, maintaining meaningful relationships). In conclusion: writing the ‘serial killer’

Is the series saying that Holden, Bill and Wendy are in fact psychopaths? Probably not. But it suggests that some of the qualities which make up a severely antisocial personality are shared by many more people than we may want to think. There’s no reason why the kinds of people we’ve been discussing shouldn’t appear in fiction. After all, they represent an extreme aspect of what it is to be human. But remember you'll need to engage with some very disturbing material if you are going to do justice to the subject and say anything new or important about it. SOME GUIDELINES FOR WRITING IN THIS AREA So if you are thinking about a character, bear these guidelines in mind: 1. Be sure that this is a topic you really want to delve into on a psychological and emotional level. 2. Sideline the phrase ‘serial killer,’ and other, similar 'thought-terminating clichés'; look behind the words and be sure you know exactly what they mean. 3. Establish that you have something genuinely meaningful to say on the subject, and that you know how you’re going to say it. 4. Do serious research into the phenomenon; otherwise, you’re at risk of recycling uninteresting, potentially damaging clichés. 5. You are depicting a human being with a personal history – not an abstract ‘incarnation of evil’ or a ‘monster’, even if their behaviour makes them seem so. 6. Bear in mind the most chilling and provocative line in the entire series. It comes from Edmund Kemper, in the course of Holden and Bill’s last interview with him. And it relates, among other things, to Wendy’s preoccupation with high-level psychopaths: “Seems to me,” he says, “everything you know about serial killers has been gleaned from the ones who’ve been caught.” About Ian Long I am especially interested in Thrillers, Neo Noir, Horror and Science Fiction, and I teach workshops in these genres as well as ones in 'Deep Narrative Design' and 'Creating Fear in Films'. A dark psychological thriller called 'Stargazer' that I have co-written with director Christian Neuman is being shot this autumn. I'm currently finishing a 'supernatural drama' set in rural Italy, and working on a number of other stories. and mentoring a number of writers on a variety of interesting projects. If you'd like to find out more about working with me, you can contact me here. AND PLEASE LET ME KNOW ANY THOUGHTS YOU HAVE ON THIS BLOG IN THE COMMENTS BELOW! AGREEMENT, DISAGREEMENT AND ALL OTHER REACTIONS GRATEFULLY ACCEPTED!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

BLOGTHE ONLY PLACE TO TALK ABOUT THE CRAFT OF SCRIPTWRITING.

|

Privacy Policy © Euroscript Limited 2020

RSS Feed

RSS Feed