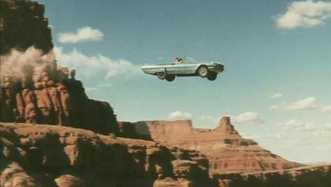

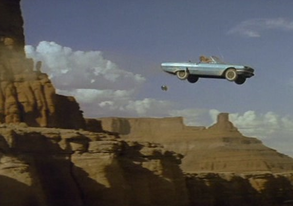

by Charles Harris Our polished new draft is almost finished - last time we gave the dialogue a thorough work out. But we're working in a visual medium. Your descriptions are even more vital - and yet many screenwriters fall down badly here, writing descriptions that are at best boring and at worst sabotage the whole script. Visual means visual Having written the best dialogue you can - now your first task is to try to cut it all out! How much do you really need? Italian writer-director Lina Wertmuller tries writing a complete draft with no dialogue at all. It may sound drastic, but it's an excellent way to force yourself into visual storytelling. Once you've done this, you can always replace those lines that you absolutely still have to have. Then it's time to make those descriptions really pull their weight in your script. The biggest mistake that writers make at this stage is either writing descriptions that are flat, over-technical and fail to bring out the mood in an interesting way. Or overwriting - as if writing a literary work, such as a novel or short story. 8 steps to creating cinema This is where you bring out the filmic quality of your story - picture and sound. Your job is to evoke the feeling of watching the finished movie or TV show - with economy and power. Re-read each scene in turn, seeking out: 1. Dialogue that can be replaced with visuals (or sound) Can that line of beautiful, witty, moving dialogue be better expressed in a cinematic way? Often a thought, mood or idea can be more strongly evoked by an action, a look, an off-screen sound effect or some similar piece of cinematic storytelling. Instead of someone saying how angry they are, for example, we can see them crumple up a letter or hear them hammering a nail into a piece of wood. 2. Descriptions that are in the wrong place Writers who've read a number of stage plays might be tempted to use the theatrical convention where scenes open with detailed descriptions of the stage layout. However a screenplay must only give what's dramatically relevant at the time. Don't start a scene with a lengthy description of the location. Set the scene with a single pithy sentence and then move straight into action. INT. LECTURE THEATRE - DAY In the vast hall, long lines of chairs wait, empty. MARK checks the time on his watch... If a prop, such as a lectern, is going to be needed later - then you can safely leave it out until it's needed. 3. Novelising By contrast, novels and short-stories tend to describe scenes in great detail throughout. This too doesn't work for a script. You may want to describe the bustle of the railway station, with those interesting odd-ball passengers, the ramshackle coffee stall, the sun slanting through the glass roof... But if it's not dramatically relevant you absolutely must cut it out. Screenwriting is closer to haiku - a single well-chosen detail stands for the whole. 4. Mind-reading At the same time, you can only describe what could be filmed (or recorded on sound). So cut out all lines which tell us what someone is thinking, or remembering, unless the audience could reasonably work it out for themselves. Lines such as: He stares out of the window remembering that this is the view that his ageing aunt would have seen just three days before she was arrested.... 5. Editorialising Similarly, you can't make editorial comments such as Politics are a nasty business. Instead, see if you can find an inventive cinematic way to make it clear what one or more of the characters are thinking. For all his dialogue skills, Aaron Sorkin is also brilliant at finding visual ways of conveying characters' thoughts. 6. The bleeding obvious Delete anything that would be obvious from the context. If it's raining, you don't need to say that people are sporting coats and umbrellas. If the scene is a courtroom, we can assume there are seats, lawyers, a judge... For the same reason, you shouldn't ever say that your protagonist is beautiful or fit. When did you ever see a movie where the star actors weren't! Only include such things if they go against expectation - your hero doesn't have an umbrella in the rain, the hero is a fat slob, etc. 7. Locations that don't deliver Many writers choose the first locations that come to mind and stick with them. But those first thoughts are rarely very exciting. Look at each setting and ask yourself if it's adding the most it can to your scene. Does that action have to take place in an office, or living room, or restaurant? What about somewhere more unusual and evocative? Such as a graveyard, or the avionics bay of a jumbo jet, or in the middle of a martial arts class? 8. Descriptions that don't evoke Finally none of your descriptions should be flat, dull or cliched. Good screenplays bring a moment to life in a short, freshly-minted phrase. For the same reason, ditch technical directions such as camera shots. These should be avoided because they break the mood. Use your originality and your language skills to the full to evoke character, location, atmosphere, action so that we get the feeling - from high tension to romantic bliss. But keep it brief. In the next episode... By now your script should be really tight. Story, structure, characters, scenes, dialogue and descriptions the best you can make them. There's just one big thing that needs to be done before you get it ready to send out. Indeed, the next draft could turn out to be the most important of all. And that's the subject for next time. Charles Harris is an international award-winning writer-director. His book Complete Screenwriting Course reached the Top Two in Amazon's bestseller list for TV scriptwriting and has been in the Top Nine for cinema scriptwriting for many months now. <previous next>

1 Comment

Charles Harris Scenes are the powerhouse of a screenplay - but too often they fail to grip their audience. This is due to a fundamental mistake that many writers make without realising. Conflict or dilemma? Everyone knows that a good scene needs external conflict - what most writers don't realise is that the external conflict is only half the story. At the heart of every good scene is a dilemma. A dilemma is essentially a situation in which your protagonist must make a choice between two equally bad alternatives. Without it your external conflict will remain superficial and uninvolving. Say, for example, your heroine is afraid of heights. She must save a child from falling to its death but can only do it by crawling onto a high ledge. Her inner dilemma draws us in. Either she stays safe, but loses the child, or she takes a risk and faces her worst fear. We want her to make the right decision - but at the same time we're afraid for her. Once she has made her choice, she is then plunged back into external conflict - lets say the ledge is slippery, the child difficult to grasp - which takes us to the next step in the story... and a new dilemma. Different stories This cycle of conflict and dilemma is by no means confined to high-tension action scenes, it comes into all kinds of scenes and genres. Take a recent episode of the legal drama series The Good Wife. Alicia Florrick's fledgling law firm has no money to pay for an assistant and so she's been relying increasingly on her teenage daughter, Grace. Grace willingly takes on a fight with their landlords but that leads to a dilemma when Alicia realises that her daughter is spending too much time on the company and sacrificing her own life. Alicia is faced with two bad options: jeopardise the firm or jeopardise her daughter's future. But she can't avoid the issue. She must make a decision and she must make it now. The choice she makes leads to her a fresh conflict - she has to confront Grace. Which in turn leads to a new dilemma. And so the cycle of dilemma and conflict continues... Your own scripts If written with energy and truth, alternating dilemma and conflict will always grip us. Now look at your own scripts. Whether planning, writing or editing, where could you bring out the dilemmas more clearly - or create them if they don't yet exist? Can you see how you could use the cycle of conflict/dilemma/conflict to strengthen your scenes? Was this tip useful? You can spend a day learning more scene-writing skills and turbo-boosting your scene-writing confidence at my workshop Creating Great Scenes in London on Saturday May 21st.  By Charles Harris Are you planning to get stuck into some writing this January? Or getting ready to polish one up for selling? I thought I'd kick off the season with ideas and techniques for using your time in the most useful and productive way. This will the first of a series that will take you through the steps from start to finish, so if you follow them, by the time you've finished you'll have a finished screenplay for film or TV - ready to send out. What kind of writer are you? To start, what kind of writer are you? There are four basic kinds (with variations): - those who plan every detail - those who prefer to jump in and see what happens - those who plan, but like to improvise when they feel like it - and those who plan but continue to change the plan so that it keeps pace with the draft as they progress. Any method is good, if it suits you and your story. However, with film and TV scripts there is much less room for jumping in blind than, say, with novels and plays. Personally, I plan the basic steps but allow myself freedom to discover and improvise as I write. This keeps the freshness, but ensures you don't go so far off piste that the whole story falls apart. Here are the first steps, so you can start on them right now if you want. Then I'll follow up in more detail in future days and weeks. By the way, the process that follows is also a great way to work with a well-developed script. It's only too easy to lose your way in a script edit - this method ensures you never lose sight of the essentials even as you polish. 1. Find your seed A good seed will make you interested, fired up, ready to explore. The problem with writing is it's like getting caught in the storm. As the story builds and you're in the middle of the storm you forget where you were planning to go in the first place. Remembering what started you off will help you keep going to the end. Most writers start with ideas that come as a seed, unformed but with the germ of interest. Usually it's an image - a man walking down a railway track in the night, a body lying stabbed in a swimming pool. Sometimes it's a character they want to explore. Who is it? What does she want? What does she need? For Harold Pinter, his seed was often a line of dialogue. Who's speaking? What will they say next? Start working on this now. Ask yourself what first excited you about this story idea. Whatever it is, locate it, write it down and begin to brainstorm. Jot down any thoughts that grow from your seed - images, places, characters, feelings, events... Write them in whatever form you like - in lists, on separate scraps or in a diagram connecting your thoughts like the branches of a tree. As you do, see what ideas begin to come. 2. Create your pitch or one-sentence log-line For the second step, we'll be focusing that core idea into a pitch that gets me fired up. I never start writing anything unless I have a strong one-sentence pitch that has that crucial spark. After all, the first person I have to sell the idea to is myself. 3. Plan the treatment or outline Later in the series, I'll talk about developing a route-map for the journey you're about to undertake. The better you make this, the more you can relax and trust where you're going. 4. Write the draft First drafts are best written fast. I'll be looking at how best to organise to do this, so that you don't get hung up on distractions and details. 5. Edit the draft Most writers make the mistake of trying to edit everything at once. I believe that the best way to eat a large sausage is one slice at a time. So in the final articles I'll be taking you through the steps from big picture to tiny detail in seven separate edits. Ready, Go, Steady Are you ready for the journey? Or maybe already in the middle of one and can do with some help and reassurance. Most people wait till they have every single detail perfect... and never start! Don't wait till you have everything perfect - the best place to start is now. Step #2 - the premise and pitch CHARLES HARRIS Charles Harris is an experienced award-winning writer-director for cinema and TV. His first professional script was optioned to be developed by major agents CAA in Hollywood and he has since worked with top names in the industry from James Stewart to Alexei Sayle. He created the first Pitching Thursday for London Screenwriters' Festival, has sat on Bafta awards juries, lectured at universities, film schools and international film festivals and teaches selling and pitching to writers, directors and producers across Europe. His new book Teach Yourself: Complete Writing Course is recommended reading on MA courses. |

BLOGTHE ONLY PLACE TO TALK ABOUT THE CRAFT OF SCRIPTWRITING.

|

Privacy Policy © Euroscript Limited 2020

RSS Feed

RSS Feed