|

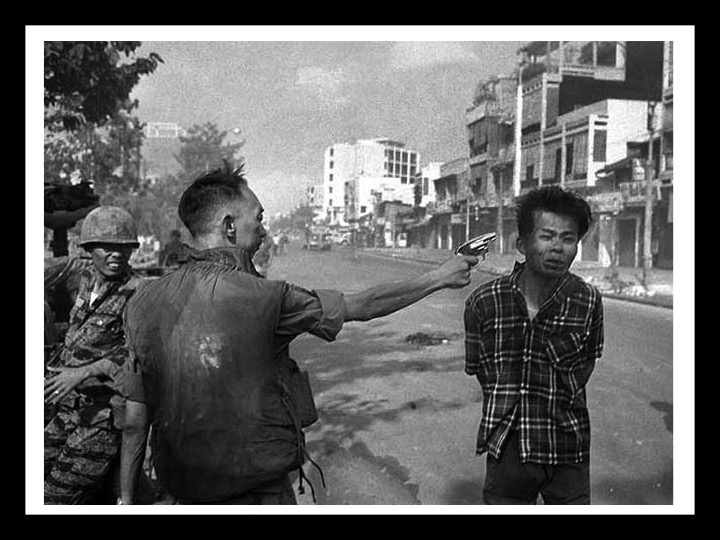

Here's a summary of Fenella Greenfield's recent talk at the London Short Film Festival 2015 about the top ailments she finds in screenplays she's asked to give feedback on. Most stories have one main central character and about four ancillary characters. If your cast list is looking like a telephone directory - prune. First act: a rom-com; middle act: a slasher movie; final act: an interplanetary showdown? If the answer to this is 'yes' join the club - genre mash-up its one of the most common problems we see in scripts. If we can't see it don't write it. For example, don't write: 'As he enters the room she remembers that childhood playground encounter when, cruelly, he shoved her from the swing.' Have mercy on the actress asked to 'act' that. Goals like, 'She believes we're on the edge of an environmental catastrophe' can't be seen on screen. A goal like, 'She's travelling to a landfill in Indonesia to research a piece for the Sunday Times Colour Supplement' can. While its true some movies are 'ensemble' pieces consisting of a gaggle of central characters, most have one strong central character who drives forward the action and is on screen at least 85% of the movie. 'But', you might be saying to yourself, 'I don't want to write some tedious agitprop, award-winning, but coma-inducing polemic' . . .

0 Comments

1. Think of your scene like a moving painting, with its own narrative, an unfolding event , with a story that unfolds through space - in the foreground, middle ground and background, and through time - with a beginning, middle and end. 2. Choreograph your visual actions like a dance of intentions. It is the interplay of two people’s desires, conscious or unconscious, a dialectic of forces, and the interchange leads to an outcome which is not exactly the intention of either, and it is a surprise. 3. Show the visual interaction between your character and their world. Use it as a metaphor for the person’s inner state, their feelings, confusions, conflicts. And when the character has a choice, a decision to make, illustrate the consideration of this decision by showing their alternatives in opposing visual ideas. 4. Think of your story like walking through an unknown building, discovering the spaces and events in each room, and then beginning to understand the architecture. Ask what happens and how it happens in each of your locations. Who else is there? How do the things happening in each room interact with your character’s story? And remember the accidental and the random is a part of life too, this opens a scene up, making it alive and credible to an audience. 5. The physical place is part of the character’s life, and their story. Where is their home? What do they feel about it? Where do they escape to? Where do they feel comfortable and where do they feel ill at ease? And they will be discovering new places, how is it that they have come there? And who do they encounter in these new places? How does it change them? |

BLOGTHE ONLY PLACE TO TALK ABOUT THE CRAFT OF SCRIPTWRITING.

|

Privacy Policy © Euroscript Limited 2020

RSS Feed

RSS Feed