|

When changing tastes and technical advances raise the bar on extreme imagery, what does this mean for narrative? Article by Ian Long Have you noticed cinema’s recent tendency to keep viewers locked onto extreme events for long periods of time? An incident that might once have functioned as a momentary shock is opened up, delved into, and transformed into what I’ve dubbed an “immersive catastrophe” - an event that plays out on a high note of terror, strangeness or personal threat for an extended duration, typically focusing on the experience of a single person. It’s interesting to speculate on the possibilities that this tendency opens up for narrative, and also what’s happening on an emotional level. Here's an example of an immersive catastrophe from the beginning of Hereafter (Clint Eastwood, 2008): A couple awakes in a hotel room overlooking a tropical beach where people swim and frolic. The woman leaves the hotel and browses some stalls in a crowded street, smiling and chatting with a young girl as she buys a bracelet. Meanwhile the woman's partner stands on his balcony, watching in disbelief as the sea draws away from the beach, then rushes back in the form of a huge tidal wave. The wave smashes into the coast, uprooting trees and crushing buildings, and surges down the shopping street towards the woman. Holding the girl's hand, she tries to outpace the water; but it overwhelms them. They’re borne along by a fast-flowing river full of cars, trees, and other debris. The woman loses hold of the girl. She’s rushed through the space beneath a wooden awning where electrical wires are shorting. A vendor’s stall is hurled on top of her and pulls her to the bottom, but she fights free. She’s slammed into a tree which has fallen into the road; grabs it; a man is poised to pull her to safety, then a car door hits her head and knocks her under the surface. Heartbeats are heard as she floats unconscious, gazing unseeingly as debris floats above her. The bracelet falls from her fingers. Her face fills the screen, then a close-up of her left eye.  Boy soldier deafened in an air raid: Come and See (Elem Klimov) Boy soldier deafened in an air raid: Come and See (Elem Klimov) Cut to black. The heartbeats stop. Hereafter uses CGI, brilliantly in this case, to model the destructive power of water in an enclosed setting and to put us into the experience of someone who is caught up in it. The pace of events is shockingly fast, and we feel how it is to be in the power of something much stronger than ourselves. Who Uses The Immersive Catastrophe? Filmmakers from Steven Spielberg and Clint Eastwood to Gaspar Noé and Lars Von Trier have embraced it. In fact, the narratives of Noé’s films Enter the Void and Irréversible each constitute one long immersive catastrophe. The shower scene in Psycho is a precursor, but in its strong form the immersive catastrophe is something relatively new, enabled by the willingness of audiences (and censors) to accept ever more extreme imagery, and the technical ability to render such scenes with great realism. Does it represent film's acknowledgment of a new audience raised on ever-more-realistic first-person computer games - and the growing talk of a convincing virtual reality experience via systems like Oculus? Quite possibly. It’s probably also related to film’s need to differentiate itself from TV, and to give cinema audiences unforgettable, inimitable experiences. We can now be subjected at length to events that would once merely have been glimpsed or hinted at, or would have proved impossible to put on the screen realistically. But what does the immersive catastrophe do? 1) It lets us share a character’s shock at the abrupt onset of a frightening event. 2) It obliges us to inhabit their experience, rather than simply watching it, as the event plays out. We tend to remain inside a character’s experience, on a very visceral level. 3) It gives us very strong visual and emotional content, and a turnover of heightened images and sensations, often of an extreme or taboo nature. 4) These incidents may occur so rapidly that they’re hard to process; or they may show us a single thing happening in great, slowed-down detail. 4) Typically, it exceeds our expectations. And this happens, even in a negative way, there can be an exhilarating element to the experience. The sheer momentum of Hereafter’s opening scene has elements of the carnival ride, for instance. 5) It glues us to the screen, grabbing our attention and heightening our responses to the larger narrative as it unfolds. 6) It burns itself onto our memory. If we’ve had a peak experience, good or bad, we’ll remember the film in which it occurred. 7) It throws everything around it into sharp relief. What is the meaning of a world that can contain this event? How does the rest of the story measure up to it? What Form Do They Take? The nature of a “shock moment” changes, taking on new meanings, when it doesn’t stop but carries on … and on … and on. Through its brutality and sheer duration, for instance, the rape scene in Irréversible becomes a personal and emotional catastrophe not just for Alex, the woman who has been assaulted, but also for the audience. Its impact just wouldn't be the same if it had been shorter. By being forced to experience the event in real time, we too feel trapped, overwhelmed, subject to a malign will that can't be reasoned with. Our nerves are stretched to breaking point. Irréversible also demonstrates that immersive catastrophes needn’t always play out on a large scale, with the aid of special effects. As with Hereafter, a “grammar” has to be found to structure the mini-narrative of the immersive catastrophe. When a single event is stretched out, it inevitably becomes a series of smaller events - bound together by the unities of time and action. Positioning in the Narrative

The immersive catastrophe also takes on very different meanings depending on its position in the narrative. Catastrophic events usually spell endings. The play Journey’s End by R. C. Sherriff ends with the cataclysmic death of all the characters we’ve seen, bringing home the fragility – close to meaninglessness - of individual histories in war. However, an extreme, “everything is over” scene at the beginning of a film can mark its seriousness of intent. If stories dealing with war and other kinds of inhumanity are going to be truthful to their subject, shouldn’t they be brutally honest from the outset? An “ending event” in the middle of a film (Psycho, Irréversible) inevitably serves as a fulcrum for the narrative, a “game-changer” which throws the audience and may even alter their sense of the genre of the story they’re watching. Many would argue that terrors evoked in viewer’s minds are still more powerful than anything we actually see, no matter how catastrophic – but filmmakers now have the licence to explore a different, more bruising and arduous kind of fear, and they need to think about how it works. Creating Fear in Films workshop - April 16 We'll be looking further into these and many other ideas, and the deep psychology of fear in all kinds of cinema, in our workshop in Central London on April 16. Places are very limited, so book now to avoid disappointment! You can find out more here.

10 Comments

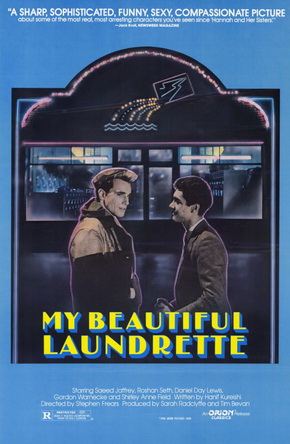

Co-Chairman and Co-Founder of Working Title Films, Tim Bevan has made more successful movies than any other producer in British cinema, and created what is effectively Britain's only major studio. Charles Harris interviewed him for Euroscript at the BFI. Article and Illustrations by Ian Long “Be bold,” says Tim Bevan, smiling at the throng of attentive faces in a jam-packed BFI Blue Room. “You have to have a ‘take.’ It’s better to fail triumphantly than be boring. I don’t want to see bland movies.” This was the final takeaway from a conversation during which they’d arrived as regularly as sushi in a well-run Japanese restaurant. It’s easy to see how Tim has enthused so many of our leading directors, writers, actors and financiers with his projects for more than thirty years. Cutting a seemingly languid figure in shades of grey and chocolate-brown desert boots, he nevertheless has the ability to cram volumes into his engaging flood of information – and to make it all interesting. The Blue Room was rapt. Beginnings To kick off proceedings Charles offered a brief question about the early days of Working Title and Tim was away, giving us a whistle-stop tour of its beginnings as a music video company, the (not always successful) decision to get established film directors involved in the making of pop videos, and then the big step into feature production. “Channel Four went round all the theatres in Britain, getting the resident playwrights to write something,” he said. And from this process emerged Hanif Kureishi’s story of middle-class suburban Asian life, homosexuality, and the automated washing of clothes – “a world we knew nothing about.” My Beautiful Laundrette was a big success, and over the next few years the company made a string of well-received features. All seemed set fair. However, there was a big ‘but’ coming with respect to the early days of Working Title. The Development Process “We weren’t spending enough time on scripts,” Tim admitted. “To be in this business properly you need to develop scripts, work on them for a length of time. But you also have to be able to get to the end of the process and say, ‘it’s not good enough to make.’ Even after £800,000-worth of development. Better an £800,000 hit than an £8,000,000 hit. Quality control starts at the beginning and goes all the way through – that’s something we learned from Stephen Frears.” Ah yes, Frears – the multifaceted maverick who directed Laundrette, and the quintessential writer’s director: a man who prizes screenwriters’ contributions so highly that he actively wants them on set, providing tweaks and rewrites, rather than hoping they just go away once they’ve delivered their final draft. Perhaps it was indeed Frears’ influence that led Working Title to place writing at the very centre of its endeavours, and to put so much energy into the development process. But where do the stories come from? Tim said Working Title tends to source its stories from three main areas:

The Story Process If an interesting project arrives with no writer attached, a list of possible screenwriters will be drawn up – “new, mediocre and high-end” - the idea will be circulated to them, and when the right person shows interest, they’ll be asked to prepare a short (two-page) document outlining their ideas for the shape of the story: the overall feel, and how the acts will divide. Meetings will then be held to get a strong sense of the story’s genre and hooks, perhaps ‘carding’ it on a wall with colour coding for different kinds of scenes (action, romance, etc). After this, the first draft is expected to nail down the main journey or arc; the subsequent development process will mainly be concerned with “making the story come alive.” Writers' Rooms Increasingly, Working Title is making use of writers’ rooms to brainstorm story ideas for their films – just like American TV series. “The dividing lines between the various writing disciplines are getting more and more blurred,” Tim said, admitting that if he could change one thing about the way he operated in the past, he'd use TV as a platform for getting films made. Writers’ rooms are also useful for getting “new blood” into the company – something which is evidently important to Tim, as he used the phrase more than once. Interestingly, he feels that British theatre is currently more vibrant than either film or TV; producers routinely visit fringe and other productions in search of talent. He also thinks that a new British comedy genre could be on the verge of arriving, which will eclipse the present vogue for gross-out humour. The Future

Looking ahead, Tim cautioned that due to the ubiquity of digitalisation, “the old model won’t exist in ten years.” He went on to speak about the competition posed to films by flat-screen TVs in homes, and the availability of high quality, low cost stories on streaming services like Netflix. All this means that companies like Working Title must become ever more stringent about quality control. “We have to be so much stricter now,” Tim said. Certain story elements are de rigeur: “As a writer, you need an amazing hook. And there has to be a ‘movie-star’ part.” Tim advised writers to "be hard on their own material," offering the example of Joel and Ethan Coen as film-makers who are so disciplined in their writing, storyboarding and shooting that they rarely need to cut anything. He also spoke approvingly of a director he’s currently working with who, even while outlining a nascent story, is already thinking about ‘trailer moments’; bits of action that will sell the finished film in cinemas. Tim Bevan is clearly passionate about films and stories – he stressed that he’s always been driven by getting good work made, rather than obsessing about ‘The Deal’ - but it was sometimes hard to square his dictum to “be bold” with the ever tighter demands that he sees commercial considerations making on material. No doubt this contradiction is something that he is struggling with, along with everyone else creatively involved with film. However, the good news about the new digital world in which we’re now immersed is its insatiable need for content. And, as Tim put it, “the new model will play far more than ever before to the individual.” One Last Tip - The Cutting-Room Reminding us of the wisdom that films are made not once but numerous times, at the stages of conception, writing, shooting and, finally, editing, Tim advised writers to get deeply acquainted with the last process on the list. “One of the critical things for a writer to do is to get into the cutting-room,” he said, explaining that it’s through witnessing the editor's craft, standing at her elbow, that the “power of the image” is revealed – and we see how whole scenes can be discarded in favour of a single glance or gesture. Tim told us that Richard Curtis is one writer who haunts the cutting–rooms of the films he works on. And it doesn’t seem to have done his career any harm. |

BLOGTHE ONLY PLACE TO TALK ABOUT THE CRAFT OF SCRIPTWRITING.

|

Privacy Policy © Euroscript Limited 2020

RSS Feed

RSS Feed