|

How to plan and write your next script - 3

by Charles Harris In the first two parts of this series on writing and editing your script for cinema or TV, I focused on the seed image that starts it all, and the premise or pitch that provides the dramatic fuel (re-read them here). Now we move to writing the treatment (aka synopsis or outline). 1. Writing a treatment is by far the best way to plan out your script in advance It’s true that some writers dive in and fly by the seat of their pants, but they are rare and almost always writing novels. A screenplay is much tighter and will run away from you if you don't plan. I have only written one successful screenplay without a treatment to start (and even then I spent time sorting out my ideas while I tried and failed to!) 2. Writing a treatment is invaluable for rewriting Once the first draft is done, you need to stand back and get perspective. Otherwise you get lost in the mess. I find that the best way by far is to go back and rewrite the treatment based on what I have now learned. 3. Writing a treatment is essential for selling More and more producers and agents insist on seeing a treatment before they’ll consider reading your script. It doesn't matter how brilliant your writing is - if the treatment doesn't fly, the script will never even get read. However, the good news is that you don’t need to write three kinds of treatment. The effort entailed in ensuring your writing is clearly understood by others will make it all the better for planning and editing too. Starting the treatment If you followed the last article and worked up a strong log line then you have a solid basis to build on for the treatment. You know your genre, the protagonist and his or her main story goal. Treatments can be of any length - from half a page to 30 pages or more - though most range from two pages. (the length you need for the Euroscript Screenwriting Competition) to five. I find it best to start with a very short version, maybe less than a page - to help me focus. I follow with a deliberately overlong version - to allow the writing to expand. I then cut that version short again. Alternating lengths allows me to get the best of both worlds - brevity and flow. Style Write in the third person, present tense (like the script). Focus on the most important beats of the story - and as with the pitch: be ruthless. But at the same time, keep the style flowing. Allow it to reflect the genre - light-hearted for comedy, dark for horror, etc. Character Don’t forget character. A good treatment is just as much about character as plot. I find it useful to alternate sentences between character journey and outer story. This draws the reader in and also avoids the dreaded “and then… and then… and then…” Proportion Your aim is to make the treatment fit the proportions of the planned script - in other words the first quarter of the treatment should equal the first quarter of the script, and so on. This is a tough one - most of the treatments I see spend far too long on the opening, feeling that they have to explain everything. You don’t. It’s not about how much you can squeeze in, but how much you can get away with leaving out! Ending And unlike the pitch, you must include the ending. This is an unbreakable rule. No matter how much of a surprise twist you've got, you have to tell us. Without the ending, we can’t appreciate the point of the story. Or be sure you know how to end it yourself. Start now. Focus clearly on your story, the unfolding of key events, the development of the inner journey and how it all comes together at the end. Create treatments of different lengths - you’ll need them later. And make your writing sizzle. Next: Writing the first draft If you liked this article, Charles Harris runs Exciting Treatments for Euroscript - a one-day workshop on writing treatments for cinema and TV in February and November. He'll take you through basic and advanced techniques for writing the strongest treatments and series proposals - including language skills that you need and which aren't taught in normal screenwriting classes. This is always a popular class and gets rapidly booked up. Check here for the next available date and to see if there are still places available.

0 Comments

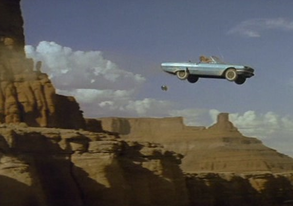

Every successful screenwriter I know is brilliant at pitching. The ability to pitch well accelerates every aspect of your career in cinema or TV - from coming up with new ideas to developing them, and of course selling them. Last time, we started by looking at your seed image. If you missed the article, read it here). This time, we’re getting stuck into the pitch or log line. Why have a pitch at the start? A good log line is essentially a one or two sentence pitch which has something magical that makes your listener’s eyes light up - this is the spark. Nowadays I never start writing a script unless I have a log line with that spark - after all the first person I have to sell the idea to is myself. As I write, and then as I edit, the pitch helps keep the script focused. And at the end, the pitch is central to selling it to producers. What’s your pitch? There’s a certain magic you need in creating a good idea that you can’t force into existence. But you can create the right conditions for finding it. And you can do that right now. You don’t have to be clever, you have to be imaginative, disciplined and committed to not accepting second-best. And you need three ingredients to make the pitch work: 1. What’s your genre? Ingredient one is the genre - in other words, what kind of story is this going to be? Will it make people laugh, or cry, or scream in horror? Or what? Genre is first and foremost about the emotion you want to create in the viewer. The seed image probably gave you a hint of that emotion. Now is the time to dig deeper into your imagination. Imagine the audience watching your work on screen. What do they feel? 2. Who does what? Ingredient two in a good pitch is the Outer Story. Who is your protagonist and what does he or she want? Focus on the big decision that underpins the whole story. In Hamlet it’s the decision to avenge his father’s murder. In Joy it’s the decision to invent a self-wringing mop. It’s an “outer” story because we have to film it - in other words it’s not just inside their head. 3. What’s their flaw? By contrast, ingredient three is the Inner Story. What is the inner flaw that’s stopping the protagonist from progressing? On its own, the outer story is rather thin and mechanical. This inner struggle gives it depth. Hamlet has to conquer his fear of taking action (he fails to do this in time, which gives us a tragic ending). Joy has to learn to stand up for herself. If, she does that she’ll earn her happy ending. In some stories, you find a mix, part growth, part failure, giving a bittersweet end. Put it together To create your pitch, put them together: GENRE plus OUTER STORY plus FLAW. Hamlet is a revenge tragedy about a young prince who must avenge his father’s murder but must confront his own fears before he can confront the murderer. Joy is a comedy-drama about an insecure but ambitious young woman who sets out to invent the world’s first self-wringing mop and must learn to stand up for herself if she’s to succeed Where’s the rest? Where’s the rest of the play? The brilliant writing? The subtle interrogation of philosophy? The other characters? The subplots? They don’t belong here. Don’t confuse the log line with the script. The job of the pitch is simply to excite - to excite you enough to write the screenplay and then to excite producers enough to read it! That simple sentence can take hard work to write. You need to focus hard on the absolute essentials, and cut away everything else - your 90+ page idea boiled down into a single line. But if you get it right, it will form the foundation of everything you do next - whether that’s writing the outline, editing a draft - or indeed selling it. Next: Writing the treatment.  By Charles Harris Are you planning to get stuck into some writing this January? Or getting ready to polish one up for selling? I thought I'd kick off the season with ideas and techniques for using your time in the most useful and productive way. This will the first of a series that will take you through the steps from start to finish, so if you follow them, by the time you've finished you'll have a finished screenplay for film or TV - ready to send out. What kind of writer are you? To start, what kind of writer are you? There are four basic kinds (with variations): - those who plan every detail - those who prefer to jump in and see what happens - those who plan, but like to improvise when they feel like it - and those who plan but continue to change the plan so that it keeps pace with the draft as they progress. Any method is good, if it suits you and your story. However, with film and TV scripts there is much less room for jumping in blind than, say, with novels and plays. Personally, I plan the basic steps but allow myself freedom to discover and improvise as I write. This keeps the freshness, but ensures you don't go so far off piste that the whole story falls apart. Here are the first steps, so you can start on them right now if you want. Then I'll follow up in more detail in future days and weeks. By the way, the process that follows is also a great way to work with a well-developed script. It's only too easy to lose your way in a script edit - this method ensures you never lose sight of the essentials even as you polish. 1. Find your seed A good seed will make you interested, fired up, ready to explore. The problem with writing is it's like getting caught in the storm. As the story builds and you're in the middle of the storm you forget where you were planning to go in the first place. Remembering what started you off will help you keep going to the end. Most writers start with ideas that come as a seed, unformed but with the germ of interest. Usually it's an image - a man walking down a railway track in the night, a body lying stabbed in a swimming pool. Sometimes it's a character they want to explore. Who is it? What does she want? What does she need? For Harold Pinter, his seed was often a line of dialogue. Who's speaking? What will they say next? Start working on this now. Ask yourself what first excited you about this story idea. Whatever it is, locate it, write it down and begin to brainstorm. Jot down any thoughts that grow from your seed - images, places, characters, feelings, events... Write them in whatever form you like - in lists, on separate scraps or in a diagram connecting your thoughts like the branches of a tree. As you do, see what ideas begin to come. 2. Create your pitch or one-sentence log-line For the second step, we'll be focusing that core idea into a pitch that gets me fired up. I never start writing anything unless I have a strong one-sentence pitch that has that crucial spark. After all, the first person I have to sell the idea to is myself. 3. Plan the treatment or outline Later in the series, I'll talk about developing a route-map for the journey you're about to undertake. The better you make this, the more you can relax and trust where you're going. 4. Write the draft First drafts are best written fast. I'll be looking at how best to organise to do this, so that you don't get hung up on distractions and details. 5. Edit the draft Most writers make the mistake of trying to edit everything at once. I believe that the best way to eat a large sausage is one slice at a time. So in the final articles I'll be taking you through the steps from big picture to tiny detail in seven separate edits. Ready, Go, Steady Are you ready for the journey? Or maybe already in the middle of one and can do with some help and reassurance. Most people wait till they have every single detail perfect... and never start! Don't wait till you have everything perfect - the best place to start is now. Step #2 - the premise and pitch CHARLES HARRIS Charles Harris is an experienced award-winning writer-director for cinema and TV. His first professional script was optioned to be developed by major agents CAA in Hollywood and he has since worked with top names in the industry from James Stewart to Alexei Sayle. He created the first Pitching Thursday for London Screenwriters' Festival, has sat on Bafta awards juries, lectured at universities, film schools and international film festivals and teaches selling and pitching to writers, directors and producers across Europe. His new book Teach Yourself: Complete Writing Course is recommended reading on MA courses. |

BLOGTHE ONLY PLACE TO TALK ABOUT THE CRAFT OF SCRIPTWRITING.

|

Privacy Policy © Euroscript Limited 2020

RSS Feed

RSS Feed