Your Next Script #11 By Charles Harris We're almost there. Over the last ten articles we've developed an idea, worked it up as a treatment, written a first draft and revised it to the point when it's almost ready to send out. But there are two more crucial tasks yet to perform. And the first will often make the most dramatic difference of all. What have you been putting off?This is what I call the X factor. Nothing to do with reality TV, the X factor is both simple yet profound. But only you know what that is. It could be something you've been meaning to cut - such as a sequence or character you love but which you know isn't working. It could be something you know you need to add. It could be some aspect of the script that you're starting to have doubts about. Perhaps the key turning point doesn't do the job as well as it should. Or the premise doesn't totally make sense. It's the thing you've been putting off doing - draft after draft.  The difference between OK and great Listen to the small inner voice that prompts a rethink or addition. Most good writing comes from our unconscious minds. While we need to use our rational editing brain to polish it up, we also have to listen to those deeper instincts. It's natural to be afraid of the amount of work needed. But that extra work may turn out to be the most important work of all. If in doubt... What may seem a trivial change at this stage may even have profound effects. The big difference between a script that's so-so and one that sparkles is often this stage. It's now that the writers who go the extra mile reap their rewards. Kill your darlings In this draft you examine everything you are clutching onto in your script. All too often, at this stage, we find we're still holding onto the very things that we should be letting go. Be brutally honest with yourself - because if you're not I can guarantee that the industry will be. You only get one chance with each possible buyer - producer or agent. Once they've rejected your screenplay, they are very unlikely to look at it again. If in doubt, cut it out So if you have doubts about anything, cut out the scissors. Cut it out and see what happens. (Remember you can always put it back again... But you almost certainly won't). If in doubt, put it in The corollary to cutting what you are thinking of cutting, is to write what you've been avoiding writing. What about that twist that you keep mulling over and putting off because it would involve some extra research? Or the character change that you can't put out of your head, but means rethinking the entire second act? Or maybe there's a seemingly trivial issue that you just can't put out of your mind. What are you shying away from? Changes I've made in this final mini-draft have always brought major improvements. Whether it's writing an emotional crisis that I've been shying away from, because it will be too gruelling (or challenging) to write or rectifying what seems to be a relatively trivial plot hole, I never regret this last run through. One script of mine came to life in a totally unexpected way, simply because I followed the little voice that told me I had to dramatise a flashback from a character's childhood in Jamaica. Even though I thought I was being stupid - we'd never afford the budget for a location shoot in the Caribbean - I wrote the scene. And it worked. Despite my fears, we shot it, for almost no money, on a gloriously sunny day by turning a gravel pits in Hertfordshire into a totally convincing country road near Kingston, Jamaica, and it gives a very special lift to the whole film. Listen to your instincts To sum up: you may think that all the writing is over. But you can be sure that there are a few little loose ends still to be investigated. Now, for one final time, you will gain enormously from listening to your instincts and making those last few changes that make all the difference to your script. We're almost done. One more job to do before we can send it out - which we'll look at in the final article of this series. Charles Harris is an international award-winning writer-director and best-selling author. His new novel - The Breaking of Liam Glass - is to be published by Marble City tomorrow. <previous next>

3 Comments

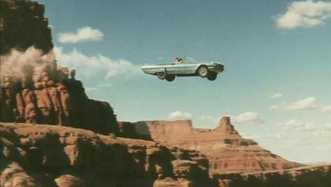

by Charles Harris Our polished new draft is almost finished - last time we gave the dialogue a thorough work out. But we're working in a visual medium. Your descriptions are even more vital - and yet many screenwriters fall down badly here, writing descriptions that are at best boring and at worst sabotage the whole script. Visual means visual Having written the best dialogue you can - now your first task is to try to cut it all out! How much do you really need? Italian writer-director Lina Wertmuller tries writing a complete draft with no dialogue at all. It may sound drastic, but it's an excellent way to force yourself into visual storytelling. Once you've done this, you can always replace those lines that you absolutely still have to have. Then it's time to make those descriptions really pull their weight in your script. The biggest mistake that writers make at this stage is either writing descriptions that are flat, over-technical and fail to bring out the mood in an interesting way. Or overwriting - as if writing a literary work, such as a novel or short story. 8 steps to creating cinema This is where you bring out the filmic quality of your story - picture and sound. Your job is to evoke the feeling of watching the finished movie or TV show - with economy and power. Re-read each scene in turn, seeking out: 1. Dialogue that can be replaced with visuals (or sound) Can that line of beautiful, witty, moving dialogue be better expressed in a cinematic way? Often a thought, mood or idea can be more strongly evoked by an action, a look, an off-screen sound effect or some similar piece of cinematic storytelling. Instead of someone saying how angry they are, for example, we can see them crumple up a letter or hear them hammering a nail into a piece of wood. 2. Descriptions that are in the wrong place Writers who've read a number of stage plays might be tempted to use the theatrical convention where scenes open with detailed descriptions of the stage layout. However a screenplay must only give what's dramatically relevant at the time. Don't start a scene with a lengthy description of the location. Set the scene with a single pithy sentence and then move straight into action. INT. LECTURE THEATRE - DAY In the vast hall, long lines of chairs wait, empty. MARK checks the time on his watch... If a prop, such as a lectern, is going to be needed later - then you can safely leave it out until it's needed. 3. Novelising By contrast, novels and short-stories tend to describe scenes in great detail throughout. This too doesn't work for a script. You may want to describe the bustle of the railway station, with those interesting odd-ball passengers, the ramshackle coffee stall, the sun slanting through the glass roof... But if it's not dramatically relevant you absolutely must cut it out. Screenwriting is closer to haiku - a single well-chosen detail stands for the whole. 4. Mind-reading At the same time, you can only describe what could be filmed (or recorded on sound). So cut out all lines which tell us what someone is thinking, or remembering, unless the audience could reasonably work it out for themselves. Lines such as: He stares out of the window remembering that this is the view that his ageing aunt would have seen just three days before she was arrested.... 5. Editorialising Similarly, you can't make editorial comments such as Politics are a nasty business. Instead, see if you can find an inventive cinematic way to make it clear what one or more of the characters are thinking. For all his dialogue skills, Aaron Sorkin is also brilliant at finding visual ways of conveying characters' thoughts. 6. The bleeding obvious Delete anything that would be obvious from the context. If it's raining, you don't need to say that people are sporting coats and umbrellas. If the scene is a courtroom, we can assume there are seats, lawyers, a judge... For the same reason, you shouldn't ever say that your protagonist is beautiful or fit. When did you ever see a movie where the star actors weren't! Only include such things if they go against expectation - your hero doesn't have an umbrella in the rain, the hero is a fat slob, etc. 7. Locations that don't deliver Many writers choose the first locations that come to mind and stick with them. But those first thoughts are rarely very exciting. Look at each setting and ask yourself if it's adding the most it can to your scene. Does that action have to take place in an office, or living room, or restaurant? What about somewhere more unusual and evocative? Such as a graveyard, or the avionics bay of a jumbo jet, or in the middle of a martial arts class? 8. Descriptions that don't evoke Finally none of your descriptions should be flat, dull or cliched. Good screenplays bring a moment to life in a short, freshly-minted phrase. For the same reason, ditch technical directions such as camera shots. These should be avoided because they break the mood. Use your originality and your language skills to the full to evoke character, location, atmosphere, action so that we get the feeling - from high tension to romantic bliss. But keep it brief. In the next episode... By now your script should be really tight. Story, structure, characters, scenes, dialogue and descriptions the best you can make them. There's just one big thing that needs to be done before you get it ready to send out. Indeed, the next draft could turn out to be the most important of all. And that's the subject for next time. Charles Harris is an international award-winning writer-director. His book Complete Screenwriting Course reached the Top Two in Amazon's bestseller list for TV scriptwriting and has been in the Top Nine for cinema scriptwriting for many months now. <previous next> |

BLOGTHE ONLY PLACE TO TALK ABOUT THE CRAFT OF SCRIPTWRITING.

|

Privacy Policy © Euroscript Limited 2020

RSS Feed

RSS Feed