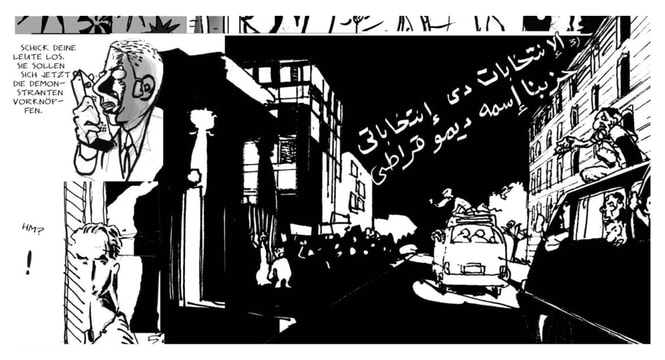

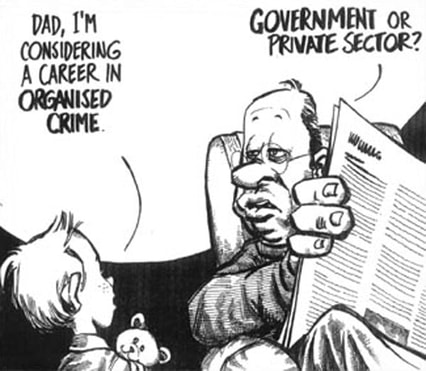

by Ian LongTo get you in the spirit for our Neo Noir workshop on August 31st, let’s explore how this flexible genre can be adapted to many different circumstances 1. NEO NOIR IS INTERNATIONAL We often see Noir as an American form – although it was made in Germany (M, 1931) and France (Pépé le Moko, 1937) years before the classic US era. As detailed in a recent BBC radio programme, there’s currently an explosion of Noir in the Arab world – particularly Egypt, Morocco, and Algeria. The themes of Neo Noir can apply to a host of settings. 2. NEO NOIR SUITS CITIES Neo Noir can be made in many settings, but it thrives on the crammed energy of cities, with their thrusting sense of modernity, money, sex, crime, struggle and corruption. Some great Neo Noir has come out of mega-metropolises like Rio de Janeiro (CITY OF GOD) and Seoul (A BITTERSWEET LIFE). Cities give the genre their own special flavour. Where's next? Which city do you want to use as a backdrop for a Noir story? 3. NEO NOIR'S A GREAT VEHICLE FOR POLITICAL THEMES Noir can shine a light on the gangster ruling classes, oligarchs and kleptocrats which are becoming ever more widespread in our world. The genre is geared to strip away the facades of organisations, revealing how the wealthy and powerful got where they are and gained what they have. 4. SOMETIMES ITS TARGETS ARE SURPRISING The shadow side of a squeaky-clean modern society is central to Nordic Noirs like THE KILLING, THE BRIDGE and BORGEN. Here, a communal rural past has been swapped for a vision of rational, state-planned ‘perfection’ – but one which threatens social and family bonds. 5. MANIFESTOS CAN HELP NOIR CREATIVITY Ingolf Gabold, head of drama at DR, the public channel responsible for the Danish TV Noirs, used a Dogma-style manifesto to shape his shows. As well as unifying the company's output and production methods, it put writers firmly at the centre of the creative process. 6. MURDER IS OFTEN THE BEGINNING OF NEO NOIR ... Tracing the process that's led to the taking of a life is often the pretext for Noir stories, answering the questions of who was involved, and what stood to be gained. But the narrative can - and must - lead in many directions. “While the protagonist is solving the case, we get to see every level of society. It’s like cutting a cake with a knife. Each layer is clearly exposed. The crime is only the beginning: we need to see how a whole society works to produce it.” - Egyptian novelist/screenwriter Ahmed Mourad And we need to ensure that the genre doesn't continue to rely on young women as stock victims. 6. ... BUT IT NEEDN'T BE Many Noirs don't feature deaths or detectives at all. Because it's the genre of compulsion and self-destruction, it encompasses stories of addiction like REQUIEM FOR A DREAM and THE LOST WEEKEND, and stories set in the gambling world like CASINO and CROUPIER. 7. Noir reaches audiences! Nordic Noir is a great example of this. Noir tropes give stories an extra dimension of anxiety and tension, whether they're about crime, sex, addiction, or other compulsions, heightening drama and increasing audience appeal. And Neo Noir can morph into many different forms to reach its audiences: films, novels, TV series and comics/graphic novels. Come to our workshop on August 31st and learn all about writing in this popular and intriguing genre.

3 Comments

By Ian LongIt isn't really a trick question, but the most important ingredient of suspense is the one thing we should always have in mind when writing screenplays:

Emotion. In other words, we need to care about - or at least empathise with - the character at the centre of the narrative, who is the subject of the suspense. (Successful screenwriting is almost always about making yourself go back to basic principles). Misery - an example of empathetic identification In MISERY (1990, directed by Rob Reiner, script by William Goldman, from the novel by Stephen King) there's only a very short time to sketch in Paul Sheldon's character before he's kidnapped by Annie Wilkes. But the filmmakers manage to give us enough clues for us to read his character and see him as someone we are willing to identify with. * Paul is an accomplished, successful novelist, which adds charisma. * He has high aspirations and isn't driven by profit; he wants to stop writing the successful 'Misery' series and do something more creative. * He has a good working relationship with his female agent, who clearly likes him. * He's caring (he wants to see his family in time for Christmas). * The hotel manager speaks well of him (we often judge people by how they deal with those in 'subordinate' positions). * He's handsome and well-dressed - but not fussily so. After the accident (which later turns out to have been deliberately staged by Kathy), there are further reasons for identification and empathy: * Crucially, Paul hasn't become a victim through greed or stupidity, or a bad decision; anyone in his position would have suffered the same fate. * He's badly injured and disoriented. * He's at the mercy of someone who is powerful, unpredictable and terrifying. * Soon after we've met him, he has become very vulnerable. * He employs great resolve and ingenuity to deal with his situation So when suspense is applied to his attempts to escape from Annie, we're "in there with him" - our emotions are fully engaged, and we're not just watching from a position of detached interest. FIND OUT ALL ABOUT SUSPENSE HERE! Although emotion, empathy and identification are the basic preconditions for suspense, there is much more to learn about this crucial aspect of storytelling. And you can do this at our SUSPENSE IN STORIES workshop. DATE AND TIME Sunday 15 April Registration - 10.15 10.30am - 5.30pm VENUE TOMPION HALL 40 Percival Street London EC1V 0HX Nearest tube: Angel MAP Click here to see a map. Click here for more, and to book. The workshop examines the changing techniques of suspense as they apply to many genres, and to films, TV series, and novels. The Tutor - Ian Long I'm a screenwriter, script editor and Euroscript's Head of Consultancy. I teach workshops in various genres (Neo Noir, Horror, Science Fiction) as well as Suspense in Stories and Creating Fear in Films.

“Look at that subtle off-white colouring. The tasteful thickness of it. Oh my God, it even has a watermark!” Comparing business cards in AMERICAN PSYCHO

Euroscript is the trusted partner of London Screenwriters’ Festival when it comes to script feedback.

Each year we help hundreds of writers at our script clinics and drop-in desk. For many, it’s the highlight of their festival – maybe because it’s the one part which is all about them and their work. Through experience, we know the dos and don’ts of attending the world’s biggest professional screenwriting event. So here are our top ten tips for a successful visit to LSF 2017. 1. Plan ahead Really study the LSF's schedule before the festival. Focus on the people you want to meet and the sessions you want to hear. Write an itinerary. But be flexible, too, and ready to catch unexpected opportunities. 2. Bring plenty of business cards… Make sure they’re printed on white card, so people can make notes about how wonderful you were after you've gone. (Subtle off-white will also work.) When you get a card from someone else, wait until they're out of sight, then make notes on it for your own use. Who they are, what they do. We guarantee you'll have forgotten your own name by day two. 3. …and network like crazy. Talk to everyone. Exchange ideas with other writers; they may become future collaborators. Pitch your stories to producers: they may get your movie made. And if they’re at the LSF, they probably want to be pitched to. But whether you’re pitching an idea to the producers’ panel, or more informally … 4. You need a script! One that you can immediately send to anyone who's interested. There isn’t much point in enthusing people with your great idea, then telling them they’ll have to wait six months while you get it down on paper. Don’t give them an excuse to forget about you.

5. And you need to have had feedback on your script.

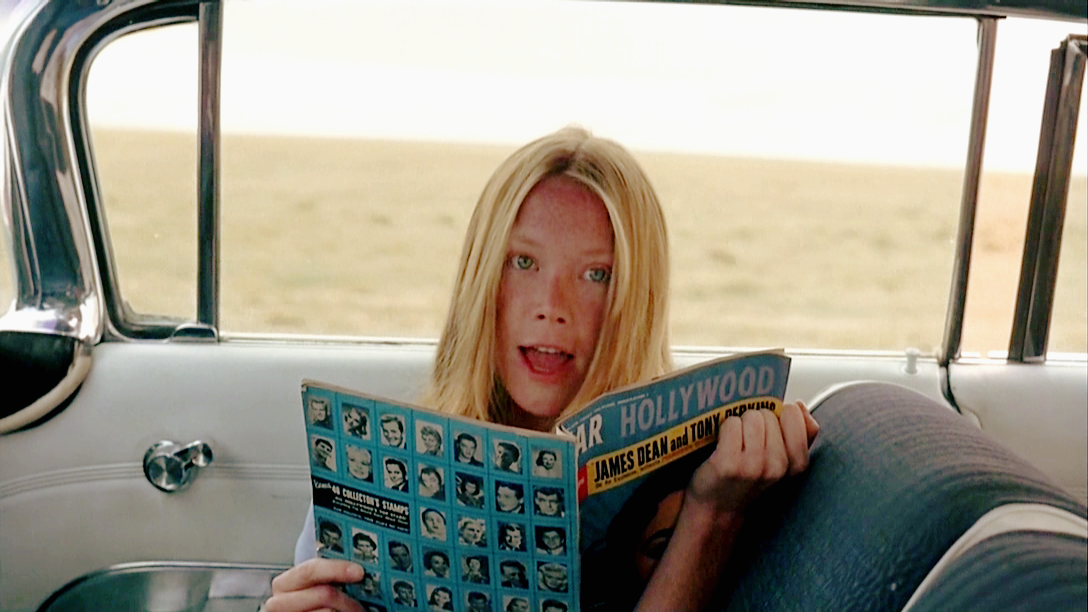

We’re not saying this just because it's our job. You really do need an objective assessment of your script's strengths and weaknesses by someone who knows what they're talking about, and to have acted on their advice, before you hand it to producers. Because you only get one chance to submit it! You can find out about our feedback services here. 6. Feedback takes time to absorb Understanding the points an editor is making, asking questions to clarify what's been said, seeing how you can creatively apply the ideas to your story - it all takes time. Many points will be made in the form of questions, throwing the creative onus back onto you, so you must allow yourself a period to reflect and revise. People often underestimate the time needed to deal with feedback. If you leave it all to the last minute, the process will feel horribly rushed. You won’t enjoy it, and your script won't benefit in the way it should. The good news is... 7. You have time to get your script in shape Now is a good time to work on your story. There’s the whole of August - and more - to get some feedback, to focus and refine your project, and also to put a great one-page outline and fluent pitch together. We can help with all this. 8. Don’t be a stranger When you come to the festival, make sure you visit us at the friendly Euroscript drop-in desk, which is open to all. You can ask questions, share triumphs or disasters, practise pitches... ...or just chew the fat about screenwriting in general. 9. Afterwards - rest, recuperate, respond If possible, don't plan anything important for at least three days after LSF. You'll crash out for the first two. Then you'll need time for following up all the contacts you made. 10. Give yourself time to debrief. Write down everything that went well - and not so well. And what you now realise you need to learn in the future. Have you got any great tips of your own for people attending the Festival? If so, please add them in the Comments below. AND SAVE ON TICKET PRICES WITH US! If you book through Euroscript, you get £23 off the price for LSF. Just write EUROSCRIPT-17X in the 'ENTER PROMOTIONAL CODE' box below. Add that up, and it's a happy £103 present from all of us at Euroscript. Meanwhile, good luck from all of us as you prepare for LSF, and we look forward to seeing you there.  Your Next Script #11 By Charles Harris We're almost there. Over the last ten articles we've developed an idea, worked it up as a treatment, written a first draft and revised it to the point when it's almost ready to send out. But there are two more crucial tasks yet to perform. And the first will often make the most dramatic difference of all. What have you been putting off?This is what I call the X factor. Nothing to do with reality TV, the X factor is both simple yet profound. But only you know what that is. It could be something you've been meaning to cut - such as a sequence or character you love but which you know isn't working. It could be something you know you need to add. It could be some aspect of the script that you're starting to have doubts about. Perhaps the key turning point doesn't do the job as well as it should. Or the premise doesn't totally make sense. It's the thing you've been putting off doing - draft after draft.  The difference between OK and great Listen to the small inner voice that prompts a rethink or addition. Most good writing comes from our unconscious minds. While we need to use our rational editing brain to polish it up, we also have to listen to those deeper instincts. It's natural to be afraid of the amount of work needed. But that extra work may turn out to be the most important work of all. If in doubt... What may seem a trivial change at this stage may even have profound effects. The big difference between a script that's so-so and one that sparkles is often this stage. It's now that the writers who go the extra mile reap their rewards. Kill your darlings In this draft you examine everything you are clutching onto in your script. All too often, at this stage, we find we're still holding onto the very things that we should be letting go. Be brutally honest with yourself - because if you're not I can guarantee that the industry will be. You only get one chance with each possible buyer - producer or agent. Once they've rejected your screenplay, they are very unlikely to look at it again. If in doubt, cut it out So if you have doubts about anything, cut out the scissors. Cut it out and see what happens. (Remember you can always put it back again... But you almost certainly won't). If in doubt, put it in The corollary to cutting what you are thinking of cutting, is to write what you've been avoiding writing. What about that twist that you keep mulling over and putting off because it would involve some extra research? Or the character change that you can't put out of your head, but means rethinking the entire second act? Or maybe there's a seemingly trivial issue that you just can't put out of your mind. What are you shying away from? Changes I've made in this final mini-draft have always brought major improvements. Whether it's writing an emotional crisis that I've been shying away from, because it will be too gruelling (or challenging) to write or rectifying what seems to be a relatively trivial plot hole, I never regret this last run through. One script of mine came to life in a totally unexpected way, simply because I followed the little voice that told me I had to dramatise a flashback from a character's childhood in Jamaica. Even though I thought I was being stupid - we'd never afford the budget for a location shoot in the Caribbean - I wrote the scene. And it worked. Despite my fears, we shot it, for almost no money, on a gloriously sunny day by turning a gravel pits in Hertfordshire into a totally convincing country road near Kingston, Jamaica, and it gives a very special lift to the whole film. Listen to your instincts To sum up: you may think that all the writing is over. But you can be sure that there are a few little loose ends still to be investigated. Now, for one final time, you will gain enormously from listening to your instincts and making those last few changes that make all the difference to your script. We're almost done. One more job to do before we can send it out - which we'll look at in the final article of this series. Charles Harris is an international award-winning writer-director and best-selling author. His new novel - The Breaking of Liam Glass - is to be published by Marble City tomorrow. <previous next> The Fatal Couple in Noir - by Ian Long As a taster for Euroscript's forthcoming Neo Noir workshop on July 8 (more details here), here's a run-down of just one aspect of the genre. "One day, while taking a look at some vistas in Dad's stereopticon, it hit me that I was just this little girl, born in Texas, whose father was a sign painter, who only had just so many years to live. It sent a chill down my spine and I thought, where would I be this very moment, if Kit had never met me? Or killed anybody..." Holly Sargis [Sissy Spacek] in Badlands, written and directed by Terrence Malick The ‘fatal couple’ who spark off something deep and dark in each other is a powerful Noir theme which continues to generate gripping new stories. In its fascination with divided natures and the tendency to self-betrayal, Noir often collapses the Protagonist and Antagonist into one person. In ‘fatal couple’ stories, though, the object of interest is a dangerous connection between two people – a connection which will probably spell the end for them (and for many of those unlucky enough to cross their path).  Homicide with a nice smile - Tuesday Weld in PRETTY POISON (1968) Homicide with a nice smile - Tuesday Weld in PRETTY POISON (1968) A morbid chemistry The fatal meeting and morbid chemistry between the couple (usually) ensures their doom. Perhaps they really do complete each other – but in a way which enhances their latent drives towards darkness and destruction. Even though there may be love between them (or at least a strong current of sexual obsession which they regard as love), it’s toxic and destructive: a folie à deux. Alone, each individual may have remained a dreamer or thwarted fantasist. Together, they can do things they’d never have conceived of even a short time earlier. They’ve recognised each other, and that has changed everything. How does the relationship work? Many new story variations can be found by refining the exact nature of the protagonists’ chemistry:

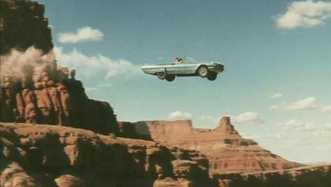

Gender variations Although the couple is often composed of a male and a female partner, interesting variations can be found when the protagonists are two males (Rope, In Cold Blood), or two females (Thelma and Louise, Bound). These can be gay or straight, or their orientation may be left ambiguous. In the case of two women, there may be an element of going up against the patriarchy and defying gender stereotypes by enjoying wild and abandoned behaviour. The sheer act of defiance represents a kind of victory, even if it leads the characters over a cliff. Q: How much thematic and narrative mileage can you find in rethinking the sexual dynamics of the subgenre? How can we find regional variations? Sightseers is a British variant on the subgenre which takes it in the direction of black comedy. The infringements which drive the couple to murder are incredibly banal, and they are themselves presented as assertively ‘ordinary’. It’s not quite clear if the couple are really angry about people disregarding the “heritage” qualities of pencil museums, trams and standing stones, or if it’s all just an excuse to unleash their own pent-up frustrations. However, the theme of an partnership that, for a variety of possible reasons, speeds its members towards darkness and doom seems relevant to all cultures (a French example is Jean Cocteau's Les Enfants Terribles, which - like Dead Ringers - concerns the toxic relationship between two siblings; Heavenly Creatures a variant from New Zealand). Using true stories American filmmakers seem more apt to base movies on their own recent history. In Cold Blood was made soon after the execution of the murderers, and was actually shot in the very locations where the real-life action had occurred a few years earlier. The Leopold and Loeb case inspired Rope and Compulsion, as well as the more recent films Funny Games and Swoon. The Moors Murders were a real-life British Fatal Couple whose story was filmed as the British TV mini-series See No Evil. Q: Can you think of more local variations on the Fatal Couple genre? Come to our NEO NOIR WORKSHOP on July 8 to find much more inspiration from this blisteringly contemporary genre. More films to check out in the subgenre: Natural Born Killers, Bonnie and Clyde, Gun Crazy, You Only Live Once, They Drive By Night... By Ian Long Is your heart filled with pain? Shall I come back again? Tell me, dear, are you lonesome tonight? Death and resurrection loom large in the legend of Elvis Presley – at least as far back as these lyrics, which he recorded in 1960. But the theme was given a new twist in Don Coscarelli’s film BUBBA HO-TEP (2002), which features an elderly Elvis (possibly the real article, possibly a lying or delusional impersonator) who is living in a residential care home in rural Texas. Elvis teams up with another inmate, an elderly black man called Jack who’s convinced that he is the assassinated President John Fitzgerald Kennedy, to fight a monstrous Egyptian mummy which is terrorising the home. Elvis: But Jack uhh, no offence, but... President Kennedy was a white man. JFK: That's how clever they are. They dyed me this colour, all over. Can you think of a better way to hide the truth than that? If all this sounds like a crazed collaboration between David Lynch and William Burroughs, that’s pretty much how it plays. It shouldn’t work – but in a strangely satisfying and even touching way, it does. And it can teach us some valuable lessons about screenwriting. What's it really about? Without giving away the story’s ending, the idea of a ‘good death’ – significant, appropriate and just – emerges as its theme. A ‘bad death’ is threatened by the Mummy, which feeds on the souls of the care home’s residents, preventing them from passing on to the next realm. Rites of Passage This theme shows that the film is a RITE OF PASSAGE story (in a Horror/Comedy mode). Many people think this genre only covers 'coming-of-age' narratives, with adolescents passing into adulthood; but our lives incorporate many transitions, which can inspire stories about:

Bubba Ho-Tep is about the last passage we undertake – from old age to death. Why Elvis and JFK?

Viewed like this, the ‘random’ choice of Elvis and JFK as protagonists makes more sense. Both men were cut down in the prime of life, Elvis in particular having made a swift transition from gilded youth to corpulent late middle-age (and ignominious death) while missing out most of the natural steps along the way. It may be too much of a stretch to give Elvis a fictional happy life. But if he's granted a meaningful death, perhaps the sour taste of his real passing can be mitigated. Why does it work? Bruce Campbell’s pitch-perfect turn as a ruefully self-critical Elvis gives the story real poignancy. Strong design and cinematography conjure up the care home's twilight atmosphere. The Rite of Passage theme brings depth and weight. But also… There’s something of a ‘conjuring trick’ aspect to this film. We’ve all heard of Elvis, JFK, and the Mummy – but surely they can't fit into a single story? Our interest is piqued, and we feel an added frisson of enjoyment when it turns out that they can. Using well-known historical or mythical figures - no matter how outlandishly - is a short-cut to audience recognition (and a useful promotional tool) …And the Mummy? The choice of the Mummy as antagonist also makes thematic sense; he’s another person who’s failed to make the final transition, is stuck in a form he should have transcended, and has become evil and monstrous as a result. Rite of Passage, Genre and Horror Horror stories can dramatise the Rite of Passage theme in especially powerful terms. For instance:

We’ll look into more deeply Rite of Passage stories, and many other narrative strategies which open up the genre, in our exciting WRITING HORROR NOW workshop on May 20. Click here to book and find out more – places are limited! By Ian Long At some level, we want (and maybe need) stories that have the power to frighten us.

Not everyone responds to full-on horror, but thrillers, war films, crime stories, supernatural tales and many other genres include extreme or frightening content. And people are drawn to them. But why? If we want to use fear in our narratives in ways that work, we should try to understand why people wish to experience this powerful, but apparently negative, emotion. So here are some reasons why people might seek out fear in films. It’s a subject which is up for debate, so do feel free to comment on the article. Maybe you can think of other reasons why people are attracted to things which - in theory - should repel them. And remember, our Creating Fear in Films workshop (Feb 25) will look at these and many other issues in much more detail. Arousal and excitement Whatever else it may do, fear gives us a strong sense of being alive and in the moment – a feeling of arousal, with an accompanying surge of adrenaline. So, terrifying as they may be in real life, frightening things can become exciting and even pleasurable in the context of fiction, where they can’t really harm us. And it’s hard to forget films that achieve this. Ritual and catharsis – and the communal experience Perhaps something special happens when we experience fear in a group setting. Going through extreme events certainly draws people together (one reason why horror movies are good for first dates?). Confronting vividly disturbing fictional events can also have a powerfully cathartic effect. We’ve visited the Dark Place, we’ve made the return journey – and if the experience is shared, we have ready-made witnesses to the fact. Some writers feel that immersion in certain types of extreme imagery has a strongly ritual element: that it’s a kind of cleansing experience which gives audiences a taste of what others may find in religion. Magical thinking When we watch terrible things happening to others, there may be a sense that we’re somehow protecting ourselves against similar things happening to us. "At least I'm facing up to the possibility of evil and monsters," we tell ourselves, "I'm admitting that they're real, rather than repressing them, so maybe they'll notice that and leave me alone." Adaptive ‘futureproofing’ Or maybe it is an adaptive rehearsal – a preparation for dealing with the possible ‘future shocks’ that life may throw at us. If we rehearse the process of facing unexpected events in fantasy, perhaps we will become more resilient in real life? Learning about life - and death It's easy to criticise 'rubberneckers' who are drawn to accidents or other unfortunate events. But are they cold-hearted voyeurs, or are they simply processing the way in which chance or a momentary mistake has the power to radically alter all of our lives? Perhaps they are trying to comprehend the principles that are at work in human misfortune. And maybe stories can help people learn how to prevent such things in their own lives, or the lives of others. A holiday from morality Do we identify with the victims in frightening films – or the perpetrators? Or do we switch backward and forward, depending on the range of feelings we want to explore? At different times, depending on our mood and circumstances, we may feel like both a victim and a perpetrator. And deep down we may suspect that in the wrong (or right) circumstances we could be capable of doing extreme, criminal and frightening things. However, modern society - with its tight surveillance, rules of thought and speech and sometimes rigid codes of behaviour - doesn't allow us to indulge these tendencies, or even give voice to them. It is perhaps more constrained than we would like to admit. Perhaps at some psychological level we need proxies to carry out the unacceptable or antisocial acts that we’d never contemplate – or if we would contemplate, that we’d never allow ourselves to commit. When these things are enacted in a fantasy setting we can indulge and purge our darker drives without taking on a burden of guilt or shame. Truth Quite simply, the world can be a scary place. Being alive is often frightening. If stories didn’t reflect this reality, they would give us an insipid, inaccurate picture of life. In summary... Whatever motives audiences may have for wanting to feel fear, we need to know how to use this emotion convincingly in our narratives. Our workshop will help you understand how to do this with clips, discussions and enjoyable writing exercises. Click here to find out more, and book.  For today's guest blog we're delighted to invite Phil Gladwin, Writer, Editor, Founder of Screenwriting Goldmine Awards In the last few years we've seen screenwriting contests move ever more mainstream. There are stacks of them in the USA, and several really notable contests in the UK. Many more agents, producers and script editors are open to the idea that getting a result in the bigger contests is a legitimate part of getting the kind of momentum new writers need. Winning a contest is great, but don't get distracted and see it as an end in itself. It's really only valuable if it helps towards your real goal - getting hired as a screenwriter. What's more, these contests often charge an entry fee - and that can add up. So how do you decide how to spend your money? [I have a vested interest I must declare - in 2012 I founded the Screenwriting Goldmine Awards, so this article is written from that perspective.] 1. Does the contest have clear industry links? Look for evidence of interest and support from the industry you want to join, either directly on the judging panel, or in affiliations to agencies, particular production companies, or broadcasters. At the Goldmine we have a taken an independent stance. We have no specific affiliation, but we do have 35 senior figures from across the British TV industry who read all the finalist scripts, and who decide the eventual winner. 2. Try to check the background of the readers in the initial stages Skilled people are not cheap, so some contests will use people with little or no real professional script-editing experience to do the first pass and read the entries as they come in. You've taken months, perhaps years to write this script; do you really want it to be assessed by someone who started in the industry last week? 3. How many entries do they get? In some of the bigger American contests they get literally thousands of entries, all competing for a handful of prizes. Given that you need to win outright, or at least be in the very last short lists a couple of times, to make an agent or producer pay much attention, you have to do the maths here. Are you happy with the odds 4. Pick a contest that aligns with your aims If you really want to write massive crowd-pleasing shows for a mass market, you will probably not find a terribly receptive ear at the Channel 4 Screenwriting contest. Similarly, if you want to write a small domestic sit-com for British viewers, the odds are that won't go down TOO well with Francis Ford Coppola's Zoetrope contest. And finally one test that you should run on yourself: 5. Do you LOVE your script? If you don't think it's practically perfect, however will the rest of the world fall in love with it? Which translates practically to you not entering a script you see is a good rough sketch. If you know there are problems, but you expect the judges to see past the bits that don't work until they find the good bits, well, you may have a problem. The standard is much too high at the top of these competitions. Winning scripts tend to be technically polished well as full of brilliant ideas. Apply these tests, and you can be just a little more confident that your entry fee is being well spent. The Screenwriting Goldmine Awards run every year. We are currently accepting scripts until 31st January 2017. More information at: https://awards.screenwritinggoldmine.com  by Charles Harris Our polished new draft is almost finished - last time we gave the dialogue a thorough work out. But we're working in a visual medium. Your descriptions are even more vital - and yet many screenwriters fall down badly here, writing descriptions that are at best boring and at worst sabotage the whole script. Visual means visual Having written the best dialogue you can - now your first task is to try to cut it all out! How much do you really need? Italian writer-director Lina Wertmuller tries writing a complete draft with no dialogue at all. It may sound drastic, but it's an excellent way to force yourself into visual storytelling. Once you've done this, you can always replace those lines that you absolutely still have to have. Then it's time to make those descriptions really pull their weight in your script. The biggest mistake that writers make at this stage is either writing descriptions that are flat, over-technical and fail to bring out the mood in an interesting way. Or overwriting - as if writing a literary work, such as a novel or short story. 8 steps to creating cinema This is where you bring out the filmic quality of your story - picture and sound. Your job is to evoke the feeling of watching the finished movie or TV show - with economy and power. Re-read each scene in turn, seeking out: 1. Dialogue that can be replaced with visuals (or sound) Can that line of beautiful, witty, moving dialogue be better expressed in a cinematic way? Often a thought, mood or idea can be more strongly evoked by an action, a look, an off-screen sound effect or some similar piece of cinematic storytelling. Instead of someone saying how angry they are, for example, we can see them crumple up a letter or hear them hammering a nail into a piece of wood. 2. Descriptions that are in the wrong place Writers who've read a number of stage plays might be tempted to use the theatrical convention where scenes open with detailed descriptions of the stage layout. However a screenplay must only give what's dramatically relevant at the time. Don't start a scene with a lengthy description of the location. Set the scene with a single pithy sentence and then move straight into action. INT. LECTURE THEATRE - DAY In the vast hall, long lines of chairs wait, empty. MARK checks the time on his watch... If a prop, such as a lectern, is going to be needed later - then you can safely leave it out until it's needed. 3. Novelising By contrast, novels and short-stories tend to describe scenes in great detail throughout. This too doesn't work for a script. You may want to describe the bustle of the railway station, with those interesting odd-ball passengers, the ramshackle coffee stall, the sun slanting through the glass roof... But if it's not dramatically relevant you absolutely must cut it out. Screenwriting is closer to haiku - a single well-chosen detail stands for the whole. 4. Mind-reading At the same time, you can only describe what could be filmed (or recorded on sound). So cut out all lines which tell us what someone is thinking, or remembering, unless the audience could reasonably work it out for themselves. Lines such as: He stares out of the window remembering that this is the view that his ageing aunt would have seen just three days before she was arrested.... 5. Editorialising Similarly, you can't make editorial comments such as Politics are a nasty business. Instead, see if you can find an inventive cinematic way to make it clear what one or more of the characters are thinking. For all his dialogue skills, Aaron Sorkin is also brilliant at finding visual ways of conveying characters' thoughts. 6. The bleeding obvious Delete anything that would be obvious from the context. If it's raining, you don't need to say that people are sporting coats and umbrellas. If the scene is a courtroom, we can assume there are seats, lawyers, a judge... For the same reason, you shouldn't ever say that your protagonist is beautiful or fit. When did you ever see a movie where the star actors weren't! Only include such things if they go against expectation - your hero doesn't have an umbrella in the rain, the hero is a fat slob, etc. 7. Locations that don't deliver Many writers choose the first locations that come to mind and stick with them. But those first thoughts are rarely very exciting. Look at each setting and ask yourself if it's adding the most it can to your scene. Does that action have to take place in an office, or living room, or restaurant? What about somewhere more unusual and evocative? Such as a graveyard, or the avionics bay of a jumbo jet, or in the middle of a martial arts class? 8. Descriptions that don't evoke Finally none of your descriptions should be flat, dull or cliched. Good screenplays bring a moment to life in a short, freshly-minted phrase. For the same reason, ditch technical directions such as camera shots. These should be avoided because they break the mood. Use your originality and your language skills to the full to evoke character, location, atmosphere, action so that we get the feeling - from high tension to romantic bliss. But keep it brief. In the next episode... By now your script should be really tight. Story, structure, characters, scenes, dialogue and descriptions the best you can make them. There's just one big thing that needs to be done before you get it ready to send out. Indeed, the next draft could turn out to be the most important of all. And that's the subject for next time. Charles Harris is an international award-winning writer-director. His book Complete Screenwriting Course reached the Top Two in Amazon's bestseller list for TV scriptwriting and has been in the Top Nine for cinema scriptwriting for many months now. <previous next>  Charles Harris So far we've planned and drafted a new screenplay, and revised it for structure, character and scenes. Now it's time to turn to the dialogue. By leaving the dialogue so late, we can be sure that we'll be making the best use of our time. There's no point fiddling with lines in scenes that may get cut out of the final script, or for characters who may disappear. Dialogue is an important part of your screenplay. Good dialogue will lift a good story and characters onto a wholly new plane. But good dialogue also comes from character and by now we should have a much clearer idea of what makes our characters tick, and what each scene is about, so dialogue becomes much easier to edit.ajor Dialogue Flaws to Check For The 8 major dialogue flaws The best way to warm up for your dialogue edit is to read and listen to the best dialogue that's been written. There's no substitute for reading great scripts - also read bad scripts so you can recognise the main faults! Now go through each scene in turn looking above all for the following: 1. Inactive dialogue Drama is action to overcome an obstacle in order to achieve a goal. All too often, you'll find that characters speak for no good dramatic purpose. Cut out padding, such as repeated greetings, goodbyes and space-fillers that don't push the story forwards. Make sure that each line comes out of the character's desire to have an effect, most often on one of the other characters in the scene, in the face of difficulty, often provided by those same characters. 2. Lack of realism In most genres, dialogue should appear realistic. Of course, in real life speech is rambling, broken up, unclear and generally disorganised. So what we're looking for here is to give a feeling of reality, while also tidying the lines up so that they can work on screen. 3. Vagueness Similarly, cut out any lack of clarity. People may not be clear in real life, but they are generally trying to express their meaning as precisely as they can, given their abilities. 4. Attacks of the dots... In an attempt to look like real dialogue, many beginner writers resort to an attack of the dots... That is to say, each line trails off in a.... People never quite finish their... Every sentence never quite reaches its... This is a fudge and sucks energy from your screenplay. Eliminate the dots except when absolutely necessary...! 5. No subtext Good dialogue has hidden meanings. Watch out for on-the-nose lines which wear their meanings on their sleeve and try to reveal those meanings instead through subtext. In 'Juno', when Juno tells Bleeker she's pregnant, he simply says "I guess so.... What are you going to do?" No long speech could so neatly sum up his inadequacy. What he doesn't say says more than what he does. And that "you" speaks volumes too. He's passing everything onto her. (Read the whole screenplay here) See if you can let the audience understand what the characters are thinking through what they don't say as much, if not more, that what they do. 6. Going round in circles Early drafts often contain lengthy passages while the dialogue tries to find its way. Cut the filler. Dialogue such as: Let's go out. I don't know. I want to go out. Let me think about it. It'd be more fun than staying indoors. I'm exhausted. Can simply become: Let's go out. I'm exhausted. On a similar theme, look out for what I call "ping-pong." It's tempting to write in alternate lines - character A answering character B who then answers character A. But this becomes rapidly tedious and flat. Try removing the "ping" (or the "pong"). Have questions remain unanswered. And answers unprompted by a question. You'll be surprised how much your dialogue perks up and gains in liveliness and unpredictability. 7. Cliche Cliched lines really drag down your script. Cliches are imprecise, so they have an effect of blurring the story and sucking interest from your characters. It's easy to fall into such writing, because the lines seem to work superficially, but try to hunt them down and find fresher and more interesting ways for your characters to speak. Listen to how people speak in real life. Becoming an adept eavesdropper (and keeping notes where possible) is a vital skill. 8. Functional dullness Many scripts get written, and even produced, whose dialogue is totally functional but simply dull. Film and TV should be entertaining. So try to write lines which are aesthetically pleasing. A nice turn of phrase, an unusual metaphor, a crisp witticism. They all help keep the story moving and add to the fun of reading the script - and watching the movie or programme when it's finally made. Now you're motoring! Take your time. By the time you've finished this mini-draft, your screenplay should be really motoring. We have just two mini-drafts to go. Next time - all the bits that aren't dialogue: the descriptions. <Previous article Next article> Charles Harris new book Jaws in Space: Powerful Pitching for Film and TV was published last month by Creative Essentials and is already recommended reading on MA courses. You can buy it on Amazon or order it here and get the e-book version included for free. |

BLOGTHE ONLY PLACE TO TALK ABOUT THE CRAFT OF SCRIPTWRITING.

|

Privacy Policy © Euroscript Limited 2020

RSS Feed

RSS Feed