|

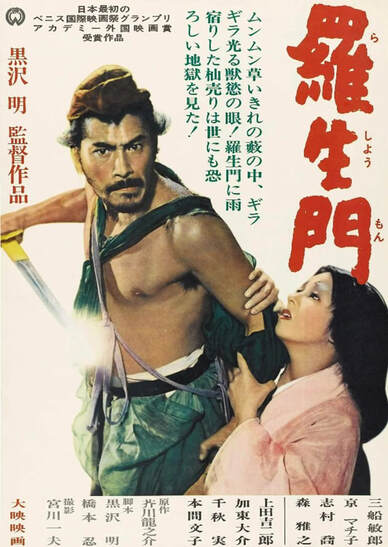

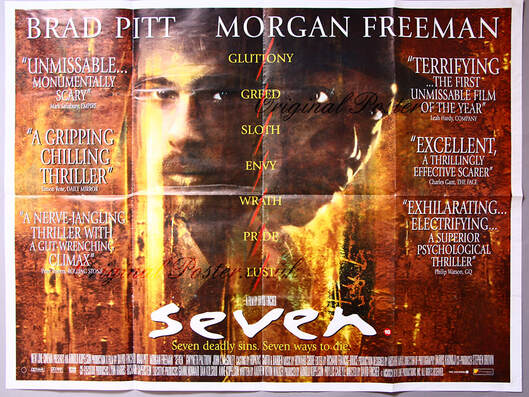

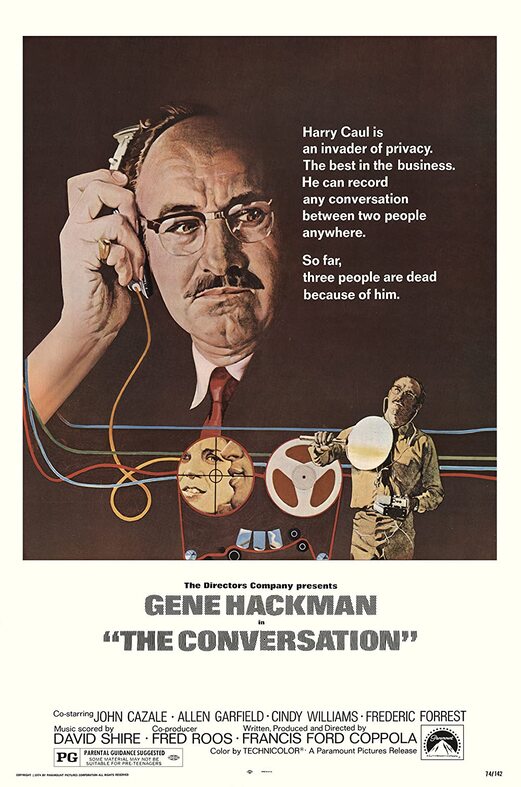

With Hollywood fixated on franchises, remakes and superheroes, writers need to look beyond the present era for inspiration. By Ian Long A top film editor recently told me that he routinely removes the dialogue from the first assemblies of feature films he's working on. He does this to see where speech can be cut and the storytelling left solely to the images. In effect, he converts the films he's editing into silent movies. This made me ponder the other things writers and filmmakers can learn from the earlier days of cinema. Later in this article we'll see how one silent drama brilliantly uses images to create its First Act Turning Point - ideas which can definitely be applied to contemporary scripts. But in the meantime . . . where should we look for inspiration? Ideally, writers are interested in all kinds of stories. A varied intake of films, plays, novels, short fiction and poetry (not forgetting real life) has always been their staple diet. But a surprising number of would-be screenwriters have a problem with older films (which can mean 'ones released before 2000'), black and white films, and silent films. Films with subtitles can also pose a challenge. Which is a shame. Because as well as a truckload of cultural heritage and plenty of interest and entertainment, these writers are missing out on a treasure-house of cinematic know-how. Why should we watch older films? The genres we work in stretch way back into cinema history (and, in many cases, far beyond it). This is because stories are mostly about the human experience, which hasn’t changed radically over tens of thousands of years. Myths and folktales still provide the basis of stories, but because the narratives of films have been configured into visual forms of a certain duration, usually by very clever and talented people, they merit special study. Film history provides a range of models for tackling subjects, and a wealth of characters, plotlines and settings to draw on, many more pointed and radical than those of contemporary cinema. Would we have seen the pitch-black satire of journalism in 'Nightcrawler' (2014), for instance, without its (even inkier) precursor 'Ace in the Hole' (1951)? What stops people from appreciating older films? Many things have changed over cinema’s century-plus existence: fashions, customs, speech and vocabulary, acting styles, special effects, approaches to cinematography and technical processes. But it’s worth remembering that some of our current conventions will seem alien to future generations, who'll need to make an imaginative effort to get past them. This effort brings its own rewards. As well as enjoying a story, we get the cognitive benefits of engaging with a reality that's somewhat different to our own. The exercise can also spur us to ask ourselves which elements of contemporary film are redundant or cliched - and perhaps look for ways to sidestep them, in order to avoid our own work seeming stilted in the coming years. Silent films Many people equate silent cinema with comedy and jerky, sped-up movements (a technical issue now being addressed; people didn’t really walk like that before 1930). But silent cinema also produced some great dramas. And it forced filmmakers to become adept at communicating ideas and emotions visually – still a crucial tool in the screenwriter's box. So let’s look at the micro-beats in the First Act Turning Point from Clarence Brown's 'Flesh and the Devil', to see what they can teach us. Flesh and the Devil (1926) In pre-WWI Prussia, army officer Leo (John Gilbert) falls in love with Felicitas, a mysterious woman played by Greta Garbo. The first act tells us a lot about Leo, but very little about Felicitas. Without fully realising it, we see her through Leo’s smitten eyes: charming, witty, beautiful, but lacking a real context - something of a fantasy-woman. Then, along with Leo, we make the shocking discovery that she’s married to a wealthy and vengeful Count, who immediately challenges Leo to a "duel of honour". The duel and its immediate aftermath constitute the Turning Point of the film's First Act. In just two minutes of screen time, director Clarence Brown and cinematographer William H. Daniels convey a lot of information with great economy and maximum emotional impact. 'Flesh and the Devil' - First Act Turning Point - Beats 1. The duel scene has no establishing shot. We cut straight from Felicitas' boudoir, where the Count has discovered Leo, to the torso of a man whose face we never see. 2. Two hands reach into frame, taking pistols from the man, who we now realise must be the referee of the duel. 3. The next shot gives us a sense of the location. But it's more like a diagram of a duel than a standard movie shot. High-contrast lighting evokes early dawn. A symmetrical composition emphasises the formality of the occasion. The Count (on the left of the referee) and Leo (on his right) are recognisable only from their silhouettes, flanked by their seconds. 4. Leo's friend Ulrich tries to dissuade him from the duel, but Leo is resolute. 5. The seconds withdraw from the firing area. 6. With the seconds out of sight, the two duellists walk away from the referee. And in a surprising moment, they keep going until they are out of frame. 7. Only the referee is visible when he gives the signal and the duellists fire at each other from off-screen. It's a very unusual way to stage a showdown. We don’t know if either man has been hit; we only see the puffs of smoke from their guns. 8. The screen fades to black, giving us a few moments to wonder what has happened. 9. The next shot gives us Felicitas’ face enclosed by a frame. She wears a dark hat. 10. A man’s hand comes into shot and pulls a veil from the hat, over her face. We realise that Felicitas is dressed in mourning, and is looking at herself in a mirror. We deduce that her husband the Count must have been killed in the duel. 11. A wider shot shows Felicitas taking off the hat and veil. A smiling assistant shows her another set. 12. Felicitas puts on the other hat and veil. And as she does, she tries out a coquettish smile in the mirror. What do we learn? Leo's killing of the Count fully commits him to the story - and to Felicitas. Until now she has been an enigma, but her demeanour when trying on her mourning outfit tells us everything we need to know about her true character. It’s all conveyed in a momentary expression, without a word of dialogue, and it gives us far more information about Felicitas than Leo has learned in over half an hour. We now know that Leo has killed a man over a woman so shallow and vain that she sees her husband’s death as a fun opportunity to dress up. It also sets up huge suspense; we are now projecting forwards in the story, wondering what will happen when Leo (if we presume he survives the duel) learns the truth about Felicitas. Will he also be subject to her lack of concern for human life? And in conclusion . . . No matter how hard we work on our descriptions and dialogue, we should rejoice if someone finds a way to replace a chunk of it with a glance or a gesture. In the end, it will make us - the screenwriter - look good. Because . . . "Show, don't tell" is the ultimate movie maxim. And the sequence outlined above is a great illustration of it. The narrative deliberately feeds us partial information (the faceless referee, the sketchy locale, the knowledge about who is killed in the duel, and just what is happening in the scene with Felicitas). By doing this, it invites us to join up the dots ourselves, and achieves the ultimate goal of the filmmaker: to make the audience feel that it is taking part in the process of creating the story. “When the present has given up on the future, we must listen for the relics of the future in the unactivated potentials of the past.” - Mark Fisher Deep Narrative Design This article represents one small section of my DEEP NARRATIVE DESIGN workshop. If you want to know more, or if you need help with a script, email me here. Share your thoughts!

Please let us know in the comments below! our summer school in brightonEuroscript's summer school is now booking! THE TV WRITERS' ROOM EXPERIENCE - 27 & 28 JULY Join a group of aspiring creative screenwriters in a simulated TV writers' room, run by writer/show-runner Anji Loman Field MORE INFO THE COMEDY WRITING MASTERCLASS - 10 & 11 AUGUST Learn how to make your material funny in any format or medium with acclaimed writer and producer Paul Bassett Davies. MORE INFO CREATE YOUR OWN TV DRAMA SERIES - 17 & 18 AUGUST Get personalised feedback, guidance and support in planning and manifesting your drama from writer/show-runner Anji Loman Field MORE INFO CLICK HERE to book all three workshops at a reduced rate. COMMENTS

22 Comments

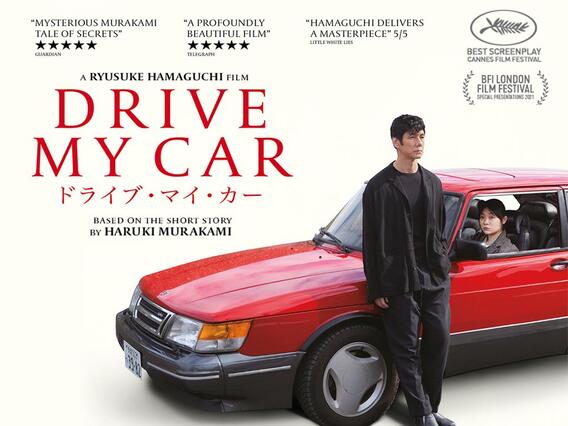

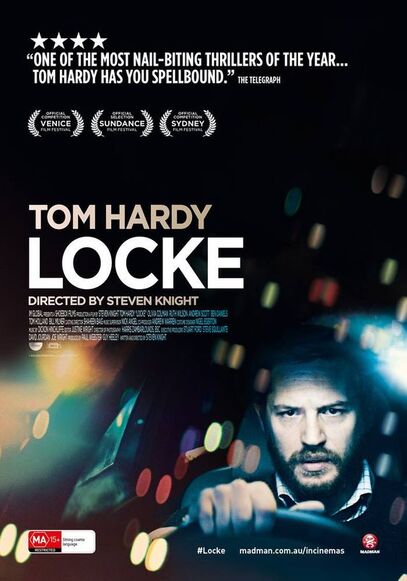

Rather than a friendly “hello”, the first utterance of the actor Errol Flynn on answering the phone was the clipped instruction “be brief.” A Hollywood star with a host of bad habits, Flynn was a busy man. But we’re all time-poor these days, which may be why the debate over film duration kicked off by Martin Scorsese’s three-and-a-half-hour Killers of the Flower Moon has had such traction. Like people, some films need a lot of time to make a point - others, not so much. The shortest-ever Oscar-nominated film, Adam Pesapane’s clever Fresh Guacamole (2012), lasts less than two minutes. Meanwhile, Gone with the Wind (1939) was four hours long and won eight Academy Awards. But when it comes to spec scripts (ones which haven’t been commissioned or solicited by producers), we advise writers to go for economy over length. And here’s why. 1. Think about the reader The person who reads your script will be busy and stressed, whether they’re a well-known producer or an intern working through a pile of submissions. The reading process requires time, concentration, and emotional investment. Readers typically check the length of a script before starting on it. If yours is well over 100 pages, they will have questions. If it's over 120, they may not read it at all. Unfair, perhaps, but true. And this reaction will only be enhanced by such things as typos on the first page – or any page, in fact. Making the reader's task manageable and enjoyable will immediately get them on your side. 2. Shorter is cheaper Film is a very expensive medium, and the longer a film lasts, the more it costs. Producers are painfully aware that every extra page of a script makes a film more expensive. So challenge yourself to tell a great story in an economical way which gets the most out of its locations and performers and has a tight page count. Doing this gives the reader several strong reasons to recommend your script. 3. An advert for you As well as a dramatic work, a script is effectively a proposal to set up a medium-sized business and an inventory of the elements needed to make it work. If it goes to production, every word will be pored over by costume and set designers, location finders, illustrators, VFX specialists, composers, and everyone else required to bring it to life. So you need to give all these things a lot of thought. Even if your script doesn’t make it to production, you can make it work as an advert for you and your abilities - a “calling card” for other writing opportunities. And turning it in at a reasonable length is a big part of this. Apart from its other merits, your script can show that you understand the medium you’re working in, demonstrate that you are practically-minded, and infer that you are likely to be a good colleague who is not prone to making crazed or unreasonable demands. A script that does all this is a better character reference than anything in your CV. 4. Length belongs to auteurs People like Quentin Tarantino, Christopher Nolan and Lars von Trier seem free to make films that run well beyond standard length. You may have ideas to rival theirs. But before you get to realise them, you’ll probably need to prove yourself first with leaner and meaner stories. If you do plan to broaden your canvas later in your career, honing your craft on compact material is the best possible preparation (see notes on Stanley Kubrick, below). And arguably, Tarantino, von Trier, Nolan and Kubrick could have benefited from a little judicious cutting at times . . . 6. Shortening your script will help improve your style Interrogate every word in your story, and get rid of all the ones that don't need to be there. Are there repetitions in the dialogue? Can you make the descriptions more succinct? Is it possible to get rid of “orphans” (single words which dangle from the end of a paragraph, occupying their own unnecessary line)? If you do this throughout your script you will shorten it by a good few pages. It will be easier to read - and you will become a better writer. 5. Stories have a natural tendency to run out of steam Scripts usually exhibit problems a long time before the 120-page mark. It's really difficult to keep up the invention within a limited scope of action, and after a certain point many stories begin to repeat themselves or strain too hard for effect. Certain genres are particularly prone to outstay their welcome. Thrillers and Horror stories which push beyond 100 pages often struggle to maintain the tension and suspension of disbelief which keep viewers engaged. And even the fizziest comedies can go flat if overly protracted. 7. Memorable longer films have found ways to overcome these problems A big budget can take a story into new settings, using something other than pure narrative to maintain audience interest. It’s worth analysing how this works in longer films that you like. Perhaps the action moves to some interesting new location, like an entirely different country; or a big set-piece like a pitched battle occurs. These episodes may take on such weight that the film’s structure could be seen as falling into more than three acts. 8. And what’s wrong with that? There’s no absolute rule that films should conform to three-act structure. But there are reasons why this form is so useful for storytelling. As more units of action are added to a narrative, it can start to feel episodic. Which means that forward momentum is lost. The story becomes repetitive and implausible. And, ultimately, boring. Great shorter films don't have to do this. So, to sum up . . . for all these reasons . . . 9. . . . it's harder to make a great long film than a great 'normal-length' film Actually, "greatness" is a matter of opinion, so we can't really verify if the percentage of great longer films is lower than the percentage of great normal-length films. But it probably is. Obviously, there's nothing at all wrong with a great, long film. Quite the opposite. Total immersion in something original, creative and entertaining is a joy. However, even hardcore cinephiles have their physical and psychological limits. And it has to be considered that . . . 10. . . . Watching a bad, long film is much worse than watching a bad, shorter film It just is. 11. “But I want to make a big statement!” A fine ambition. But longer isn’t necessarily deeper. Many commercially and/or artistically successful movies clock in under 90 minutes. Here are 16 inspiring examples.

|

BLOGTHE ONLY PLACE TO TALK ABOUT THE CRAFT OF SCRIPTWRITING.

|

Privacy Policy © Euroscript Limited 2020

RSS Feed

RSS Feed